By Tamar Eisen

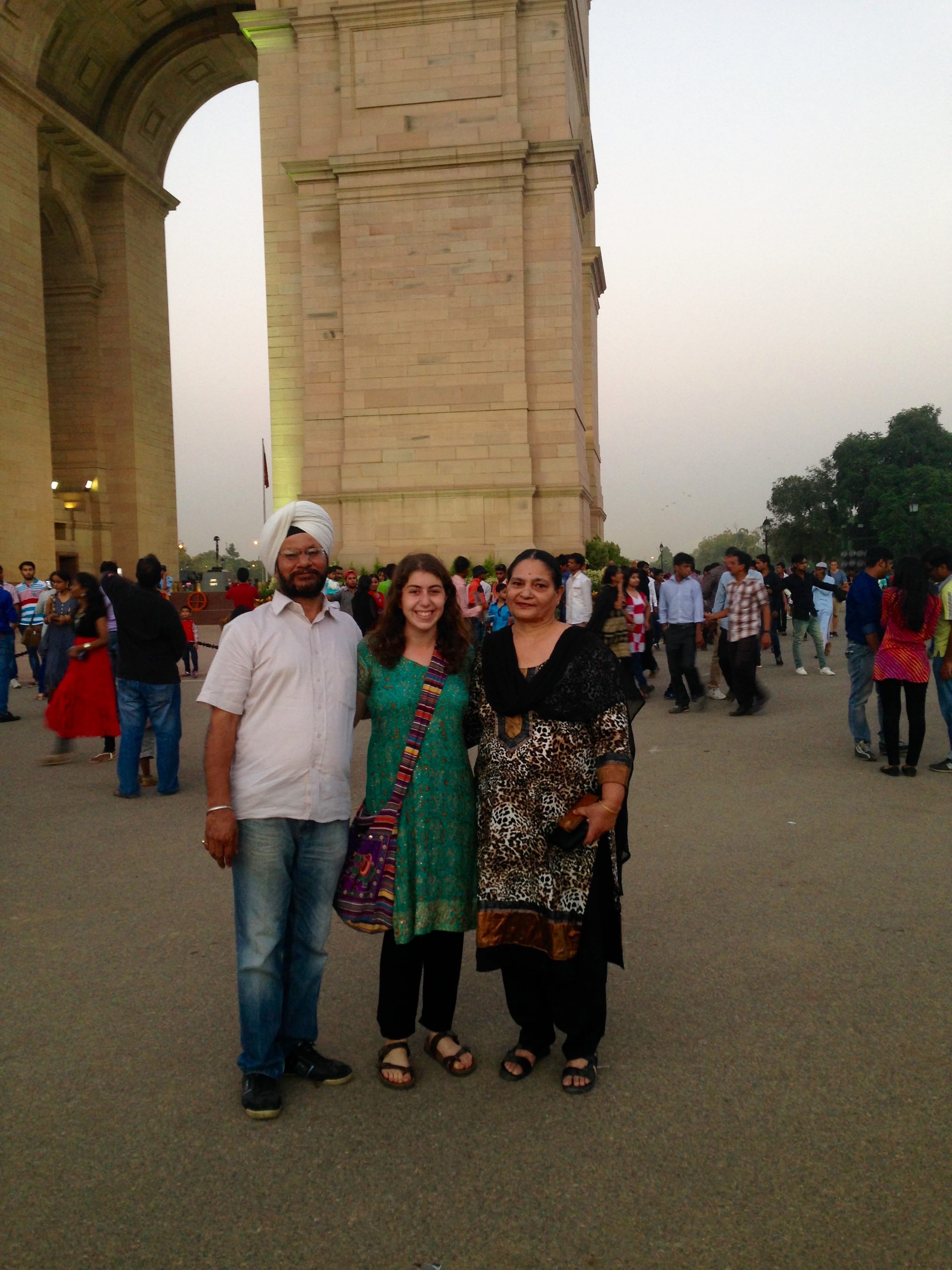

The most common question I have heard after returning to Northwestern for winter quarter is, “How was the world?” The reason I am consistently asked this question is because last fall, I went on a semester-long comparative health program to India, South Africa and Brazil. While I did reach three continents, spent time in ten different cities, and got to experience three distinct cultures, I can still say that I barely scratched the surface of the world itself. Moreover, when I try to answer this question to a friend or professor, I usually do not have time to get into the complexities and intricacies of the state of these three countries, so I tend to settle with the response, “The world was good.” I guess now that I have the space, I can delve into this answer a bit further.

In each place we visited, we obtained a comprehensive understanding of the country’s governing health system, epidemiological profile, major barriers to health outcomes, traditional healing mechanisms, public-private divide, and potential health reforms and innovations through classes and guest lectures. But no class could have prepared me for the overcrowded, understaffed, ill-equipped hospital we observed in rural India or the highly racialized nature of healthcare in South Africa or the plight of the poor living in urban dwellings across São Paulo, Brazil. An overwhelming sense of shock encompassed me as we discussed HIV, food insecurity, homelessness and violence against transgender populations in the shadows of the White House and Capitol Hill. My trip was, almost on a daily basis, a brutal confrontation with the realities of poverty, gender inequality, poor sanitation, hunger, racism, climate change, human rights violations, discrimination, and social, economic, political inequities.

But of course it was not all bad. We visited grassroots, non-profit organizations in India that worked towards better health whether it be by promoting LGBT health rights, repurposing scrap material to make female sanitary napkins, instituting children governments in rural villages, or developing compostable and economically affordable toilets. We heard stories of hope in South Africa through our conversations with the Treatment Action Campaign, who successfully fought and advocated for the introduction of anti-retroviral drugs and a universal government-provided AIDS treatment program during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We visited a Quilombo in rural Brazil – a community of individuals descending from runaway slaves – who asserted their identity to claim land rights from the Brazilian government. And we witnessed the success of Brazil’s publically funded health care system, SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde), which provides free and universal healthcare to all of its citizens.

Through these experiences I have learned to interrogate the world around me, to take a second glance at the seemingly obvious, and to embrace ambiguity and uncertainty. I’ve come to find that the world is complicated and contradictory and ironic; it can sometimes be a really awful place, but also an amazing one where people come together to create things that are beautiful.