By Nida Bajwa

Anyone who has studied global health knows that the field is wrought by many many failures, and very few successes. It is easy to get discouraged from the field when analyzing the immense amount of failure and repetition of those failures in the field. However, in analyzing these failed histories perhaps we can arrive at a greater future. As students, what is our role? What do we want to achieve from our global health education? How can we take a history of failures and turn it into success?

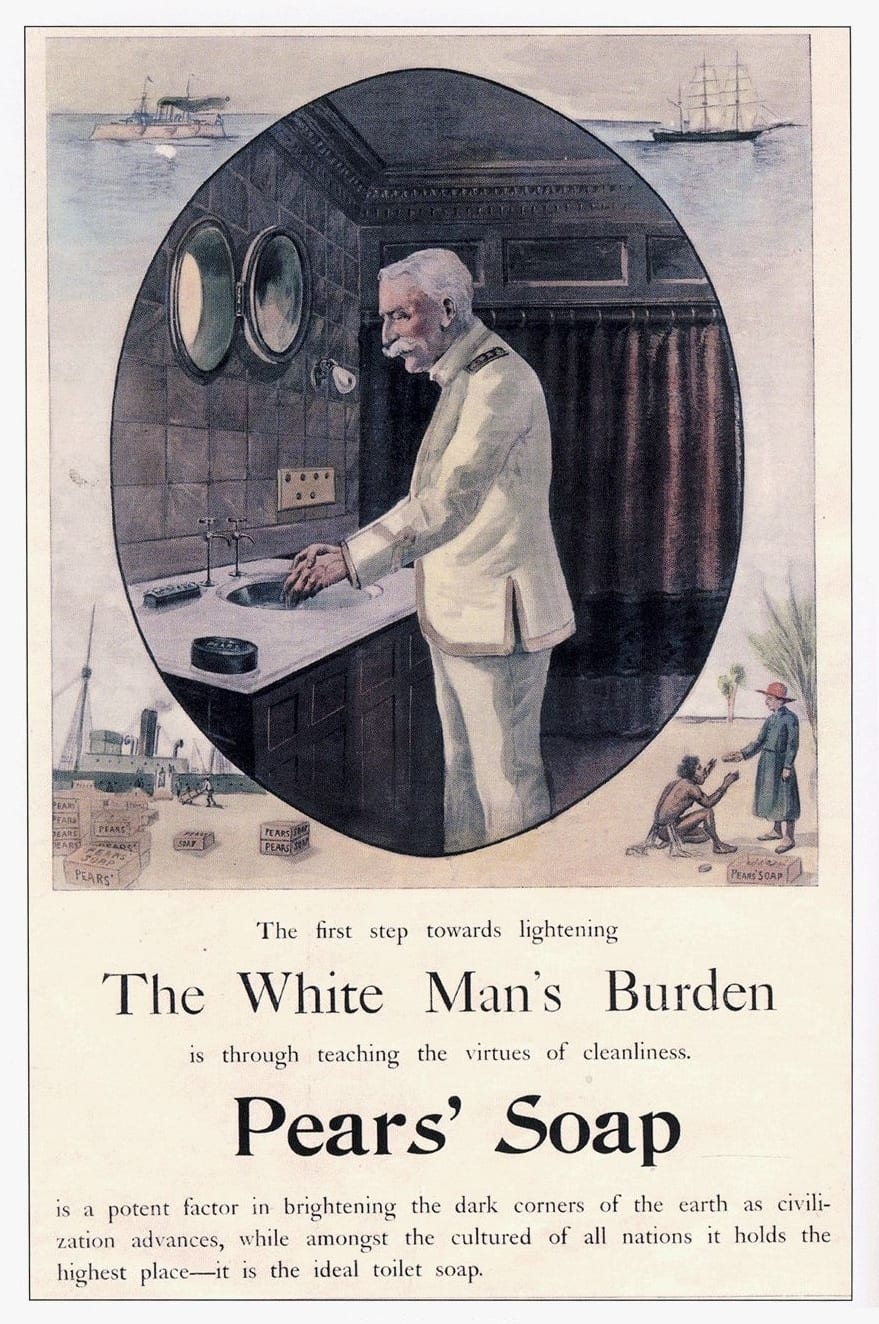

The relationship between politics and global health is immense, and can be traced back to colonialism. The commonality that exists today is that healthcare to poor, developing countries is delivered by westerners who come in and impose their set of values upon the people, an idea borne from colonialism. In some hundreds of years, not much has changed. The white man’s burden rechanneled itself into delivery of global health around the world. Similarly, racism in America has found new channels but has not left us. To this day, America is a country with institutionalized, systematic racism. That racism is the same racism of the 1600s that began slavery, the same racism of the 1950s that spurred the civil rights movement, and the same racism that spurred the Ferguson protests just months back. Similarly, global health today is still a field that is battling with that stigma, a stigma that was embedded very deeply in our colonial history.

Sadly, global health has oft been used as a tool by those in power. Interestingly enough, the mortality rates of blacks vs. whites in hot climates served as justification for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. A measure of health, associated with progress and development, thus aided in justifying a brutal system of slavery. The same determinants global health advocates use to try to do good were used to do evil. The same determinants used to grant equity in healthcare were used to justify racism, colonialism, conquest, and the lingering consequences of these institutions we are still feeling today and quite possibly will reverberate for the rest of American history. You can’t escape your colonial past, you can only work with it.

Paul Farmer, an anthropologist in the field of global health, discusses the impact of colonialism and history in an essay titled “An Anthropology of Structural Violence.” In the essay, he explains the idea of structural violence as the oppressive systems in play which all those who are engaged in take part in, perhaps subconsciously. As American citizens, we are thus responsible for structural violence, whether or not we personally engage.

So how do we, as students move forward? How do we escape America’s colonial past? The answer is uncertain, but it is clear that some form of systematic change has to occur, most likely at a political and a social level. In order to truly impact change on a health level, you have to impact change on a social scale. Until systematic racism is no longer in play, how can health ever be equal? We will have to think critically as a nation, as students, and as global citizens in effecting change and hopefully, one day, we can undo the years and years of colonialism and the damage it has caused around the world.