(co-authored with Tom Ogorzalek)

Note: This article was updated on April 10, 2020 to reflect finalized election results.

Last week, in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, Illinois held its primary election. Voter turnout was down significantly from 2016, and the presidential nomination grabbed most of the headlines. But further down the ballot, Democratic voters also re-nominated incumbent Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx in a race closely watched by criminal justice reform advocates.1 As the chief prosecutor of the county, the State’s Attorney can dramatically affect the lives of individuals and communities. This election marked the first time that a member of a recent wave of pro-reform local prosecutors has been up for re-election in a major city, and served as a barometer for local political organizations and progressive prosecutors in big cities across the country.

A Referendum on Progressive Prosecutors?

Kim Foxx rose to prominence when she challenged incumbent State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez in the 2016 election. During that election, progressive activist groups mobilized against Alvarez, who was embroiled in controversy over her handling of the murder of Lacquan McDonald, memorably creating the slogan #ByeAnita. Along with ousting a dissatisfying incumbent, these groups also sought to advance a broad criminal justice agenda through changing the policies of the county prosecutor’s office. Foxx, a former Assistant State’s Attorney and chief of staff for Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, ran on a platform of criminal justice reform that promised to reduce incarceration levels and improve police accountability measures. Amid the ongoing controversy around Alvarez, the Cook County Democratic Party reversed its initial decision not to endorse in the race and threw its support behind Foxx. In the March 2016 primary election, Foxx won the three-way race comfortably with 58% of the vote. As expected in the heavily Democratic-leaning Cook County, she went on to win the general election in a blowout with 72% of the vote.

Many citizens see elections for county-level officials as boring or unimportant, but this is a big mistake—local offices implement most of the governing in some of the most important areas of life, from education to community development. Moreover, these offices often have significant discretion in how they implement their portfolios. This is especially true for local prosecutors in the U.S., who play a pivotal role in setting the agenda for public safety priorities and making particular decisions that powerfully shape peoples’ lives. Traditionally, local prosecutors have tended to project a “tough on crime” persona and develop a reputation for harsh punishment. However, such policies may be of dubious effectiveness for actually promoting public safety, and because of pervasive biases at all levels of the criminal justice system (arrests, charges, convictions, and sentencing) have disproportionately harmed members of minority groups. These policies have subjected African Americans in particular to being simultaneously over-policed and under-policed, and have contributed to a range of racial inequities that transform the politics of such communities.

Foxx is part of a recent wave of reformist prosecutors who have advocated for and begun to implement a range of measures to reform the criminal justice system from the local level, by focusing on harm mitigation rather than punishment. Since taking office, Foxx has supported or enacted numerous reforms including bail reform, increased transparency, reduction in prosecution of low-level offenses, increased oversight for police-involved shootings, and overturning of wrongful convictions. These efforts have generally drawn praise from progressive advocacy groups and particularly from young Chicagoans most exposed to harsh policing practices. They have been opposed by police unions and suburban police leaders, while Chicago’s police commissioners have been more neutral in their evaluations.

The 2020 Campaign

Foxx’s policies and actions during her first term were controversial enough that she faced three challengers, in a down-ballot election where we might expect the incumbent to enjoy an uncontested primary. The most prominent of these opponents was Bill Conway, a former Assistant State’s Attorney under Alvarez. Conway’s campaign raised $11.9 million, including $10.5 million in cumulative donations from his father, in what turned out to be the most expensive State’s Attorney race to date. The two other challengers were Donna More, a former Assistant State’s Attorney who also ran in 2016, and Bob Fioretti, a former Chicago alderman and perennial candidate in local elections.

The handling of the Jussie Smollet controversy in early 2019 by Foxx’s office also captured a lot of attention, even if it was more attention-grabbing than attention-worthy. Foxx’s opponents and some media outlets focused prominently on the Smollett case during the election, but Foxx’s supporters saw the case as a distraction from the core issues of criminal justice reform. This race can be seen as a kind of test of how voters will respond to this agenda once in place, and whether progressive prosecutors subject to re-election are likely to successfully stay in office.

Breaking Down Foxx’s Win

Foxx won the 2020 primary comfortably, though not overwhelmingly. She won a narrow majority of votes, but the split field of opponents meant her margin of victory was nearly twenty percent.

|

Table 1: 2020 Cook County Democratic Party primary election results |

|||||

| Votes | Kim Foxx | Bill Conway | Donna More | Bob Fioretti | |

| Chicago | 514,605 | 55.4% | 27.6% | 12.1% | 4.9% |

| Suburban Cook County | 375,786 | 43.1% | 35.7% | 16.0% | 5.2% |

| Total | 890,391 | 50.2% | 31.0% | 13.8% | 5.0% |

|

Source: Chicago Board of Elections and Cook County Clerk |

|||||

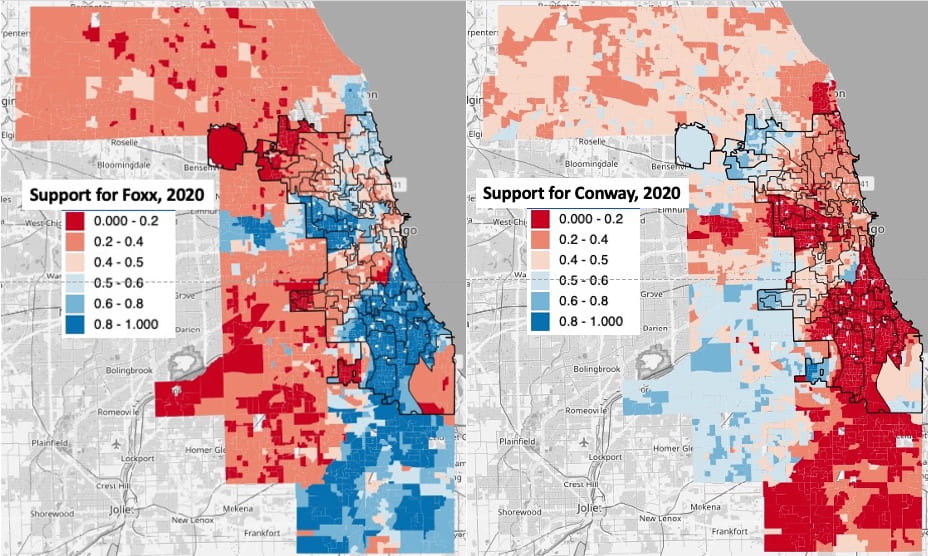

While Chicago is by far the largest single community in Cook County, there are approximately equal numbers of registered voters in the city and in suburban Cook County—about 1.5 million in each. As in other metropolitan areas, suburbanites are more likely to be Republicans or conservative than central-city residents, but in Cook County primaries Democrats still outnumber Republicans more than 2 to 1. Foxx ran stronger in Chicago than she did in the Cook suburbs, and turnout among Democrats in both places appears to have dropped significantly from 2016.

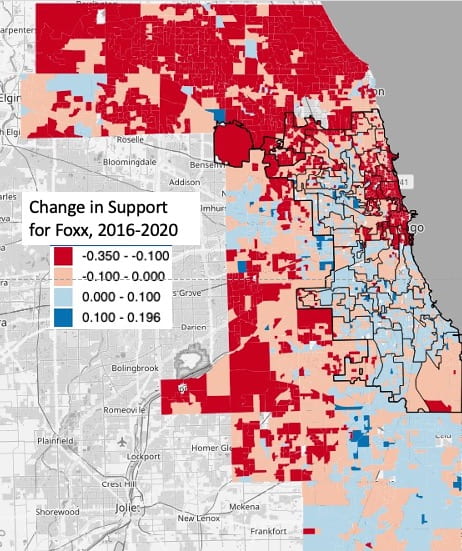

Overall, Foxx’s share of the vote dropped by about 8 percentage points (about 7 percentage points in Chicago and 9 in suburban Cook County). The map in Figure 2 below shows precinct-level changes in Foxx’s share of the vote, with redder areas showing a larger decline in support for Foxx while bluer areas indicate a larger increase in support. In large swathes of the suburbs and North Side, support for Foxx declined by more than ten percent, as indicated by the dark red shade in the map. There were few areas of large increased support over ten percent, but much of the South Side and South suburbs saw modest increases from already-strong support in 2016.

The dynamics of the races were very different: in 2016 she was a challenger to an incumbent facing a major cover-up scandal, while in 2020 she is an incumbent defending her record. The overall decline suggests that Foxx’s performance and agenda have been received negatively among some Democrats. But the larger drops in suburban support and the geographic pattern shown in Figure 2 suggest a strong racial component to the changes.

Race, Segregation, and Support for Foxx

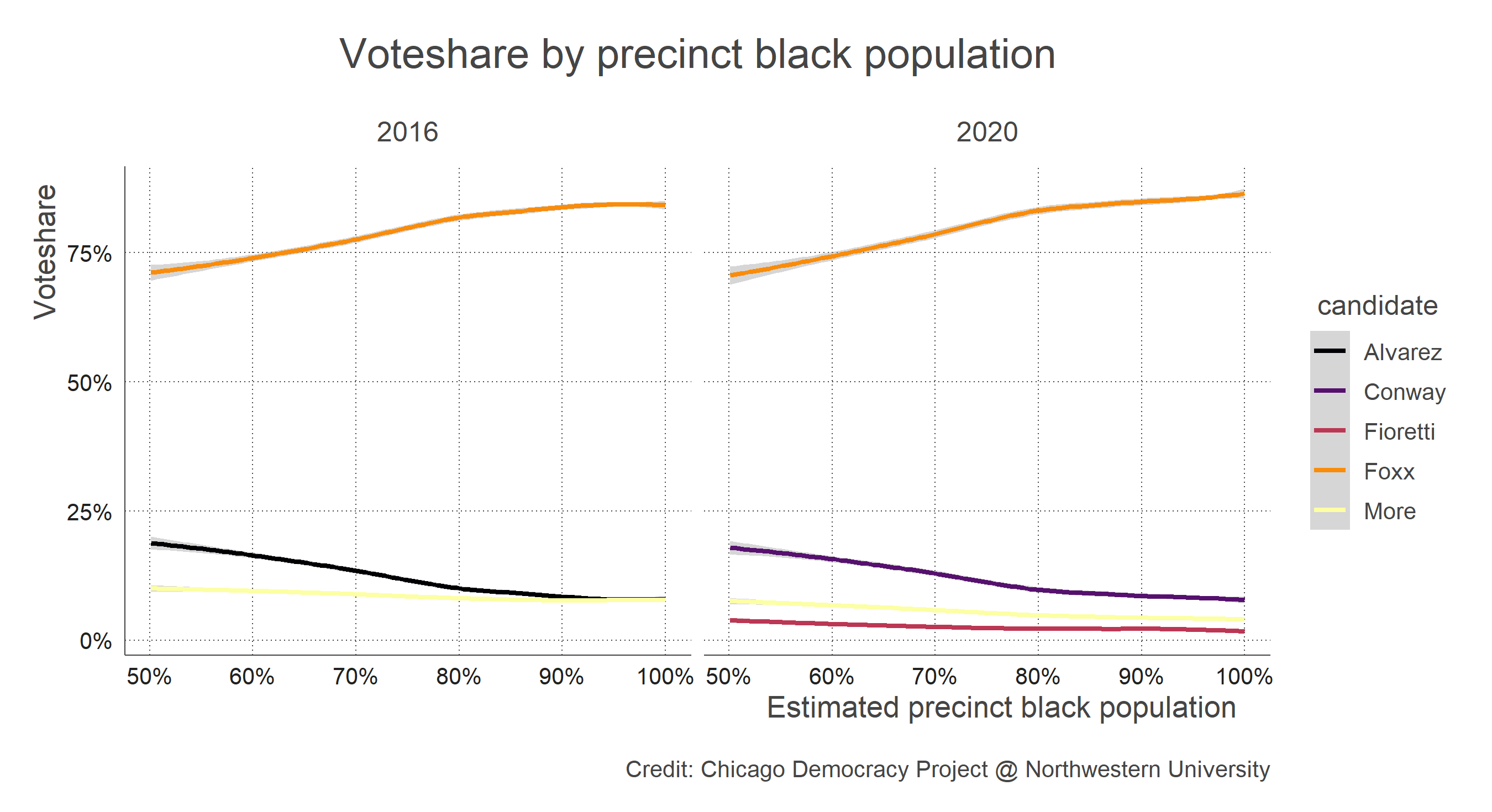

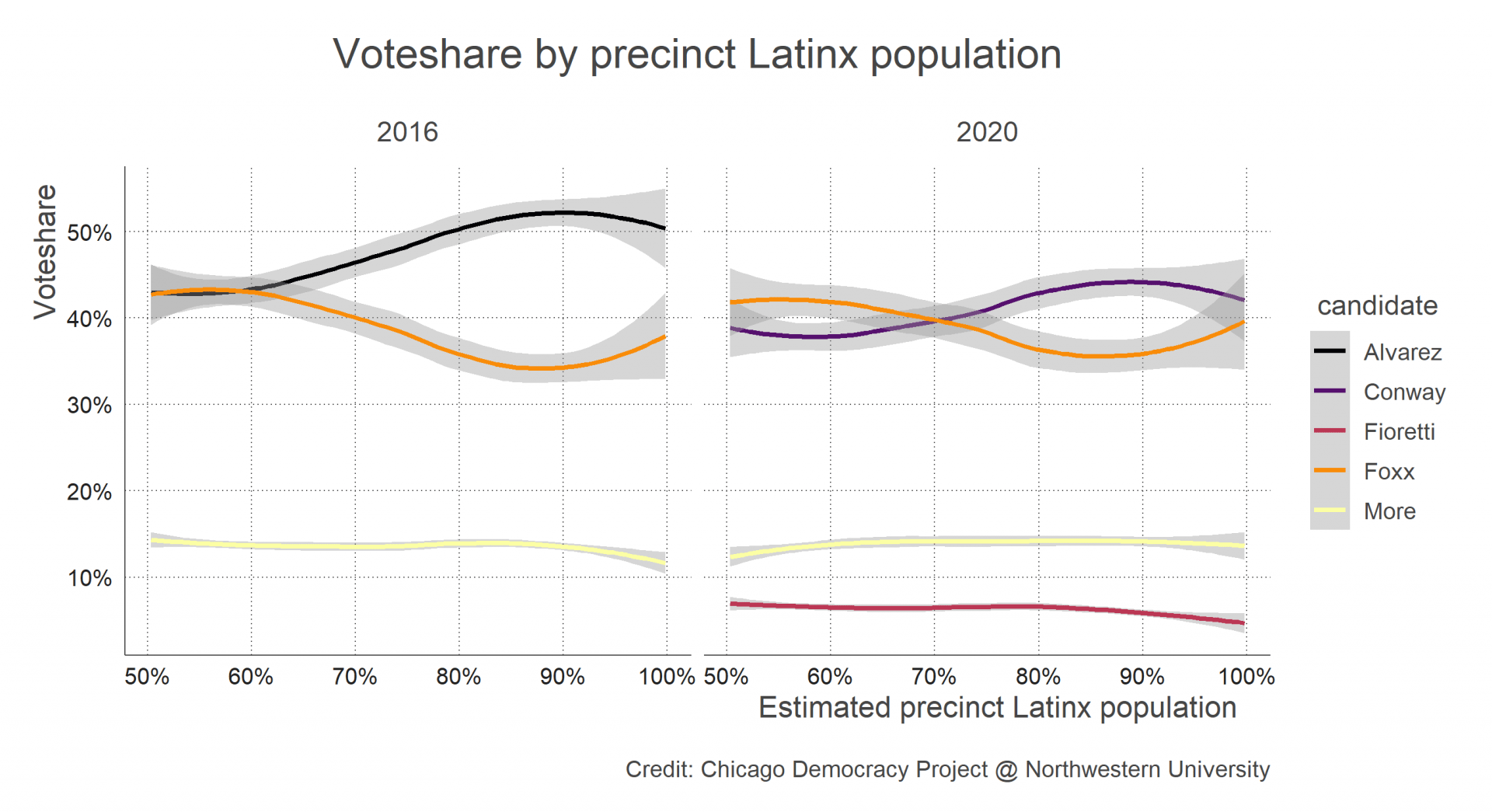

We can investigate this pattern more closely by examining how support for Foxx varies across precinct-level demographics in the 2016 and 2020 elections. We can do so by using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and processing it to estimate precinct-level racial composition.2 Figures 3-5 below show the conditional average voteshares for each candidate by precinct-level racial composition,3 in precincts with an estimated majority of white, black, or Latinx residents.4

As in 2016, Foxx ran strongest in the predominantly African American South and West Sides of the city, as well as in largely African American suburbs south of the city. Figure 3 shows remarkable levels of support—consistently over 75%—in predominantly black precincts.

As Figure 4 shows, Foxx received much less support in the white parts of the city, and Conway outperformed Foxx on average in precincts with a white population of 60% or more. Foxx experienced a significant drop in support in predominantly white precincts, although the gains from this drop were split by Conway, More, and Fioretti. There is some regional variation to this pattern: Foxx performed better in white neighborhoods on the Far North Side relative to the Northwest Side and suburban Cook County, although her share of votes declined from 2016 even in the former areas.

The story is more complicated in Chicagoland’s Latinx neighborhoods, as shown in Figure 5. While Foxx received similar levels of support on average in 2016 and 2020 in these areas, Conway did not earn nearly as much support as Alvarez did in 2016. Closer analyses show that Foxx generally won Latinx precincts on the city’s Northwest and West Sides, but generally lost to Conway in Latinx parts of the Southwest Side and suburban Cook County.

As these figures show, the geographic patterns in the results can largely be explained by the underlying demographic differences between areas. Because many elements of a criminal justice reform agenda are intended to mitigate the effects of systemic racism, it is likely that different racial groups may respond to this agenda and to Foxx, who is African American, differently.

These racial patterns also help explain Foxx’s decline in voteshare from 2016 to 2020: the decline in turnout between elections was much higher in African American neighborhoods, where Foxx found her strongest support, compared to white neighborhoods, where she saw greater losses.

On the whole, Foxx’s fairly comfortable re-nomination suggests continued support for criminal justice reform through the office of local prosecutor. However, her significant losses in predominantly white areas suggest that even in an overwhelmingly Democratic metropolitan area, white voters’ support for such measures may be less solid than their partisan preferences or national ideology would suggest.

Footnotes

- In highly Democratic-leaning Cook County, a win in the Democratic primary almost always translates into a general election win. Foxx will face Republican Pat O’Brien in the general election on November 3, 2020. ↩

- We used 5-year estimates from the most recent American Community Survey. Because Census geography and electoral precincts do not match, estimating precinct demography involve some data processing. To make these estimates, we collected ACS data for Block Groups (BGs) and used a GIS Intersect function to create a new terrain of block-group-precinct fragments across the city. The ACS count for each measure (eg. total population, or non-hispanic white persons) was divided among each BG’s fragments according to its proportion of the BG’s overall area. Then these proportionate counts were added up according to which precinct they were in, and the estimated percentages (eg. percent non-hispanic white) were created based these newly estimated precinct counts. The key underlying assumption of this procedure is that persons in the categories of interest are evenly distributed within the BG. Because BGs are small (less than half a square mile on average in Chicago), the error potentially introduced by this procedure is outweighed by the advantage of being able to compare election results to demographic characteristics. ↩

- A loess regression is used to generate the smoothed conditional means lines. For more details, see documentation here. Note that these visualizations do not account for differences in rates of registration and turnout across precincts. Analyses that do account for such variation show similar patterns. To see these analyses, please contact the author. ↩

- Though Chicago overall has no majority group, the vast majority of the city’s electorate lives in precincts with a majority group: 32% of registered Chicago voters live in majority-black precincts, 35% in majority-white ones, and 19% in majority-Latinx ones. Since only 14 precincts have an estimated majority Asian American population, generating a similar visualization for majority Asian American precincts would not yield tractable analyses. ↩

You must be logged in to post a comment.