Taking Action: Bursar's Office Takeover

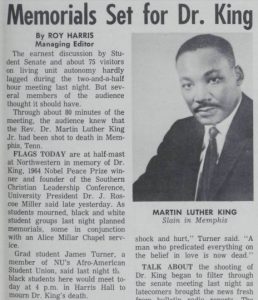

A Daily Northwestern article about memorials planned to recognize the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., April 5, 1968

The assassination of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, had a profound impact on Black students at Northwestern. As a national leader in the struggle for racial equality and economic opportunity, King’s death struck a deep emotional chord. Many Black students, particularly those from the Chicago area, returned home to grieve with their families. Across the country, King’s assassination sparked widespread unrest. Riots erupted in dozens of cities, including Chicago, where 39 people were killed and thousands were arrested.

On the Northwestern campus, a sense of unease and tension emerged. Some Black students recall walking into campus spaces and feeling the atmosphere shift, conversations stopping, rooms falling silent, as if their presence heightened others’ discomfort or fear. Yet, amid the grief and uncertainty, the Northwestern community held public gatherings to honor King. Students, faculty, and staff assembled outside Rebecca Crown Center and Scott Hall. The following day, a memorial service was held at Alice Millar Chapel, led by Chaplain Ralph Dunlap. The University closed on April 9 in observance of King’s funeral, joining in national mourning.

For Black students, King’s assassination marked a turning point. It crystallized their frustration and ignited a renewed sense of purpose. They were galvanized to speak out and demand change on campus.

In the weeks following, For Members Only (FMO) and the Afro-American Student Union (AASU) collaborated to draft a formal list of demands to present to the University administration, addressing racism and inequities Black students faced at Northwestern. Some students debated whether the document should be framed as a list of “concerns” rather than “demands.” Kathryn Ogletree, FMO President, advocated strongly for the term “demands.” To her, it conveyed the urgency and intensity of Black student’s frustration, as well their expectation that the University take meaningful action.

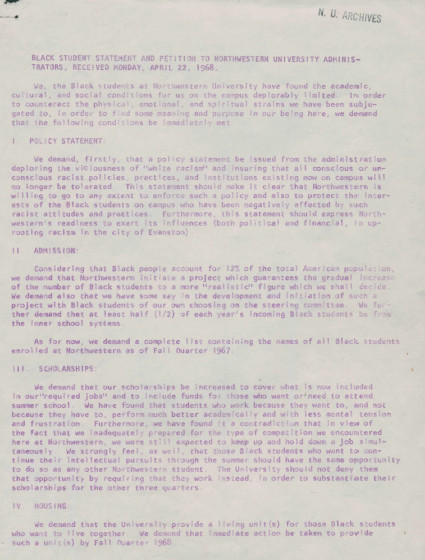

The power of language was not lost on the group. Ultimately, they chose “demands” to emphasize that their grievances could no longer be ignored or softened. On Monday, April 22, 1968, FMO and AASU presented their demands to Northwestern’s administration stating:

The Demands, April 22, 1968

The demands from Black student organizations FMO & AASU to the Northwestern University administration.

- Northwestern University present an official statement acknowledging the existence of institutional racism at the University

- Increase admission of Black students to 12 percent of the student population

- Increase scholarships for students to avoid students taking on jobs and to reduce student loans

- Offer living units for Black students who want to live together

- Add Black studies courses to the curriculum and hire Black professors

- Hire a Black counselor for Black students

- Establish a Black student union

- Advocate for open housing

The document concluded with a clear and urgent request: a formal response from the administration by 5 pm on April 26, 1968, “or else.” This closing phrase underscored the seriousness of the moment and the student’s determination to see real change. The demands were submitted to 12 members of the administration, with Dean Hinz, Dean of Students and Vice President, addressing each demand point by point.

Dean Roland Hinz, along with William Ihlanfeldt, Director of Admission and Financial Aid, and other members of the Dean of Students Office, arranged a meeting with approximately 90 Black students, including James Turner, President of AASU, and Kathryn Ogletree, President of FMO. The two-hour meeting led to the resolution of a few issues outlined in the students’ initial list of demands. However, the administration did not address several key concerns.

In response, FMO and AASU submitted a second, more detailed list of demands, further clarifying their position. Kathryn Ogletree emphasized that the administration still had a week to meet the original deadline and noted that this was sufficient time to respond. However, she warned that if the reply was unsatisfactory, “we don’t intend to keep cool.”

Dean Hinz issued another point-by-point response. On May 1, 1968, James Turner issued a formal reply on behalf of the Black student organizations, stating that they “completely rejected” the administration’s response.

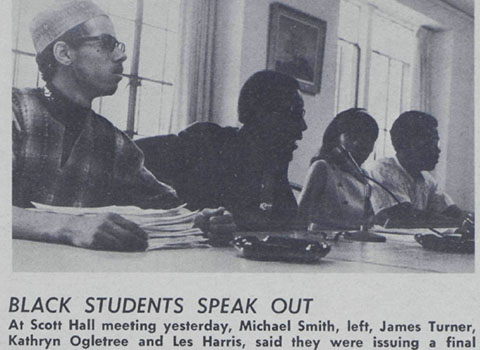

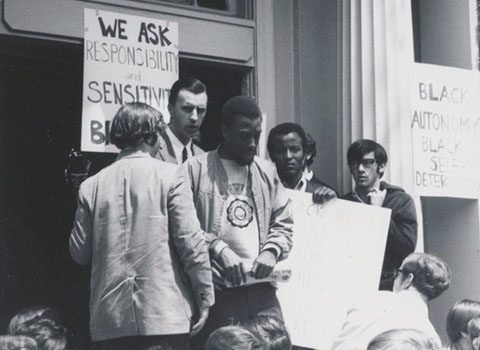

On May 2, 1968, James Turner, Michael Smith, Kathryn Ogletree, and Leslie Harris held a press conference in Scott Hall to outline a plan for a “confrontation,” giving the administration until that evening to meet the demands. In the meantime, FMO and AASU gained support from campus allies. The Student Senate, encouraged in part by sophomore Eva Jefferson, submitted a letter to the administration expressing solidarity, stating they “stood behind the idea that black students should be given a more representative position within the University community.” Support also came from white student activists Roger Friedman and Steve Lubet of Students for a Democratic Society. Lubet remarked “whenever a group of people has been exploited for 400 years like the Blacks in this country have there are no demands that should be unreasonable, they should ask for everything they can get and take.” Still, not all students supported Black studnet’s challenge to the administration.

As the administration became aware of the planned confrontation, Dean Hinz continued to reach out to Black student leaders, urging “continued communication.” That day, he met with Kathryn Ogletree to share a brief statement, one that still did not reflect a full agreement to the students’ demands. He invited them to a meeting with administrators later that evening. The students, however, declined the invitation.

Instead, FMO and AASU members met privately to discuss plans for the confrontation. Influenced by recent student protests and building takeovers at other universities, particularly at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), where some AASU members had personal connections, they decided to occupy a building. Mathematics student Amassa Fauntleroy proposed the Bursar’s Office as a strategic location because it was isolated, accessible, and of a manageable size. It was also the University’s business office, housing financial and admissions records, IBM machines, payroll, accounting, and cash reserves.

No one knew the full plan for the takeover, but every participant had a defined role. For example, Steve Colson investigated the building’s infrastructure to confirm there were no tunnels that would allow security to enter undetected. Eric Perkins and Michael Smith obtained chains and padlocks to secure the doors and prevent law enforcement from entering.

The decision to stage a takeover was not taken lightly. Students discussed the risks, especially in light of the violent police response to the Columbia University takeover just days before. They worried about being forcibly removed, arrested, or losing their financial aid and academic standing. Many came from working-class families and were first-generation college students. Some, like Eva Jefferson, were warned by her parents not to participate, or they would stop supporting her education financially. She understood her parents, and “all our parents were afraid for us.” In a collective act of protection, students agreed to excuse athletes on scholarship from participating, understanding they had the most at stake if the effort failed.

Despite the potential consequences, most Black students chose to participate, believing that they had more to gain than lose. As sophomore Leslie Harris reflected, “a lot of people paid a much higher price.” He recalled the words of his high school history teacher, Dr. Sterling Stuckey, who would later become a professor at Northwestern, who taught him Frederick Douglass’s words, “there is no progress without struggle.” Empowered by that conviction, students moved forward with uncertainty about the outcome, but resolute in their belief that they could change their university for the better. They therefore courageously took the risk.

Students in the Bursar’s Office, (L-R) Michael Smith, Steve Colson, Dan Davis, and Eric Perkins. Photo courtesy of Steve Colson.

On the morning of Friday, May 3, 1968, Black students skipped their classes and began the planned occupation of the Bursar’s Office. Aware that security guards were stationed at the building, student Victor Goode approached one of the officers outside, pretending to pick up a form from the building. However, he was gathering intel, counting how many guards were present, if they were armed, and if the doors were locked.

At the same time, a group of students staged a diversion outside of the Rebecca Crown Center, Northwestern’s central administration building. They shouted slogans and created enough commotion to draw the attention of the guards at the Bursar’s Office. The tactic worked: six guards left their posts to investigate the disturbance.

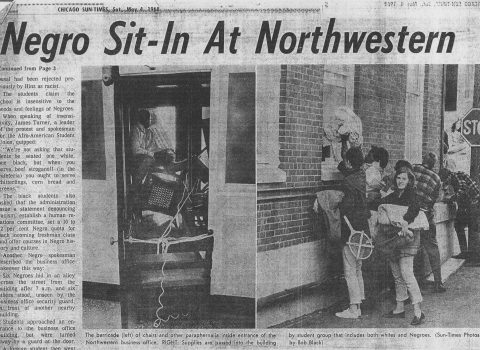

This was the signal for the students waiting nearby. They rushed to the building, chained the revolving front door, and taped a sign to the glass: “Closed for business ‘til racism at NU is ended.” Inside, they encountered a few staff members still working in the office. The students informed them of the protest and encouraged them to leave.

Within 10 minutes, more than 100 Black students entered the building, some through the back entrance near Allison Hall, others through windows, securing the space as their base for protest. The takeover of the Bursar’s Office had officially begun.

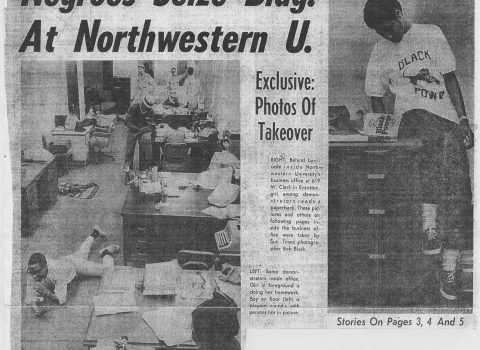

Students came prepared for a long stay inside the Bursar’s Office, bringing food, bedding, and supplies that could last for weeks; they had no idea how long the occupation might last. Herman Cage, a business student and treasurer of Tau Delta Phi, a Jewish Fraternity, used his fraternity funds to secure resources. Cage recognized the need not only for food, but also for funds in case students needed to post bail. He and Wayne Watson rented a truck from Maday Brothers and purchased supplies from a local market. Upon returning to campus, students formed a line to quickly unload the materials into the building.

As the protest unfolded, campus security returned to find the Bursar’s Office doors chained shut. Seven guards and ten security police formed a line around the building, forming a perimeter but refraining from entering. They awaited further instructions from university leadership.

About 15 minutes later, senior administrators, including Dean Hinz, Vice Presidents Kerr, Kreml, Schmehling, and Wild, Maurice Ekberg, Superintendent of buildings and grounds, and Walter Wallace, a Black sociology professor, gathered in a nearby parking lot. They later relocated to the Investment Office east of the Bursar’s Office, where they alerted Evanston Police and began a 2-hour meeting to deliberate their response. A protocol existed for handling such demonstrations:

- Ask demonstrators to vacate the premises

- Issue a formal order to leave, warning of disciplinary action

- Remove the demonstrators using the university’s security and treat them as trespassers

- Request assistance from the Evanston Police

- Execute a forced removal

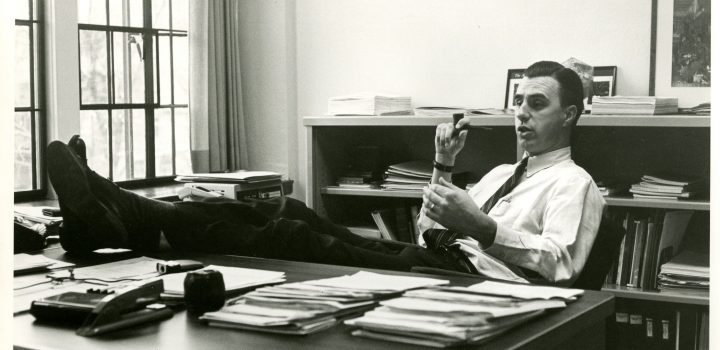

Some administrators, including University President Roscoe Miller and Franklin Kreml, Vice President of Development and a former police chief, initially supported immediate removal, noting that the building could be accessed through tunnels beneath. However, others, Dean Hinz, Dean Gregg, and Professor Wallace, urged a more cautious approach. They emphasized the risks of forcibly removing over 100 Black students, particularly amid rising racial tensions and the students’ clearly expressed grievances regarding racism, alienation, and marginalization on campus.

Kreml warned that involving police would likely result in mass arrests. The group also considered the national context: only a week earlier, a student-led takeover at Columbia University had ended in police violence, widely broadcast on national television. The racial dynamics at Northwestern added another layer of complexity, and the administrators were aware of intelligence suggesting that off-campus activists from Chicago were monitoring the situation, hoping to seize an opportunity for broader exposure.

Faced with the possibility of escalation and negative publicity, the administration reconsidered its options. Instead of following the standard protocol, they revisited the students’ second list of demands submitted on April 24, and ultimately chose to pursue negotiation with the demonstrators inside the Bursar’s Office.

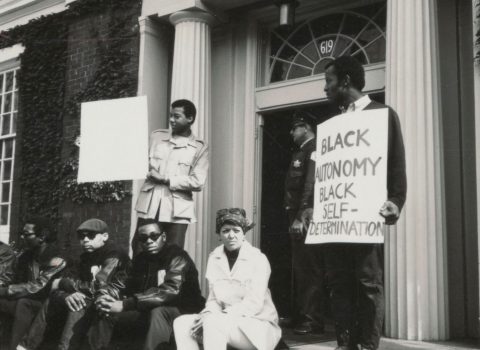

Some Black students who chose not to enter the Bursar’s Office joined the demonstration on the building’s steps, holding signs that read: “Black students occupy this building because the administration has turned a deaf ear” and “Black autonomy, Black self-determination.” The occupation quickly drew a crowd, including white Northwestern students who sat on the steps in front of the building’s entrance. Their presence served as a physical barrier, making it more difficult for police to forcibly remove students inside.

Members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), led by Roger Friedman, offered to escalate the demonstration by climbing onto the roof of the Bursar’s Office to draw more attention. However, leaders of FMO and AASU declined the offer, concerned that such a move would shift the tone of the protest. Instead, Friedman and 14 SDS members occupied Dean Hinz’s office and sent a telegram of solidarity to students striking at Columbia University.

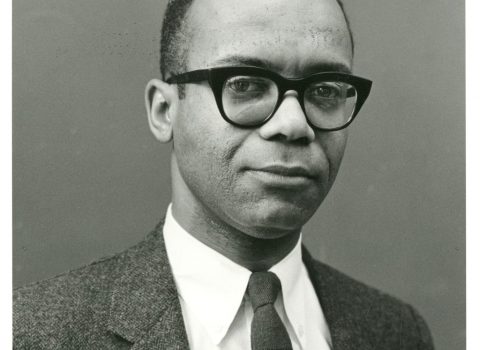

Throughout the demonstration, students remained highly aware of how they might be portrayed by the media and university officials, and were mindful of potential misrepresentation, taking steps to protect the integrity of the protest. Herman Cage, like others, entered and exited the building discreetly through a side window. During the day, he met with Professor Bennett, a trusted advisor and his business professor, as well as a retired naval intelligence officer, to discuss the occupation. Dr. Bennett offered tactical advice, urging students to remain peaceful and avoid damaging property, knowing that any misconduct could be used to discredit their cause. Cage followed through by documenting any damage and ensuring that the University would be reimbursed.

Howard F. Bennett, Professor of Business History

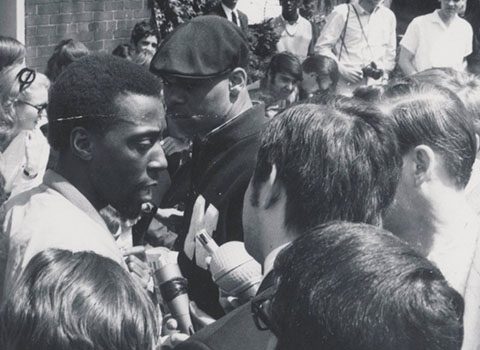

That afternoon, Dean Hinz approached the Bursar’s Office to speak with a student representative. However, those inside were wary of a possible police raid. Hinz assured them that no such action would be taken. James Turner, graduate student and president of AASU, was appointed as the chief negotiator for the students. Every couple of hours, he met with Dean Hinz in the Music Administration Building to discuss terms. Between meetings, Turner returned to the Bursar’s Office to consult with members of FMO and AASU, ensuring consensus on every update.

During his trips outside the building, Turner also addressed the media. He emphasized that the students planned to stay until an agreement was reached. Dr. Bennett shared with Cage that Bill Kerr, Northwestern Vice President of Business Affairs, kept a computer in the building containing sensitive government contract data. Turner made this leverage public, telling reporters that while the students had no plans to destroy property, if the police were sent in, he could do some damage with a bottle of Coke and Kerr’s computer.

Negotiations persisted that evening. As late as 11:30 p.m., Dean Hinz delivered a packet of documents containing the administration’s point-by-point responses to the student’s demands. Turner and the students inside reviewed the responses carefully, making edits and notes. At 12:30 a.m., Hinz returned, assuring them that he would seek input from the other administrators.

Sources

Visit the Bibliography page for sources consulted in this essay. Interviews were also conducted with the following Northwestern University alumni, Clovis Semmes, Herman Cage, Kathryn Ogletree, Leslie Harris, Jean Semmes, and James Pitts.