6. The Counterculture Years: 1967-1970

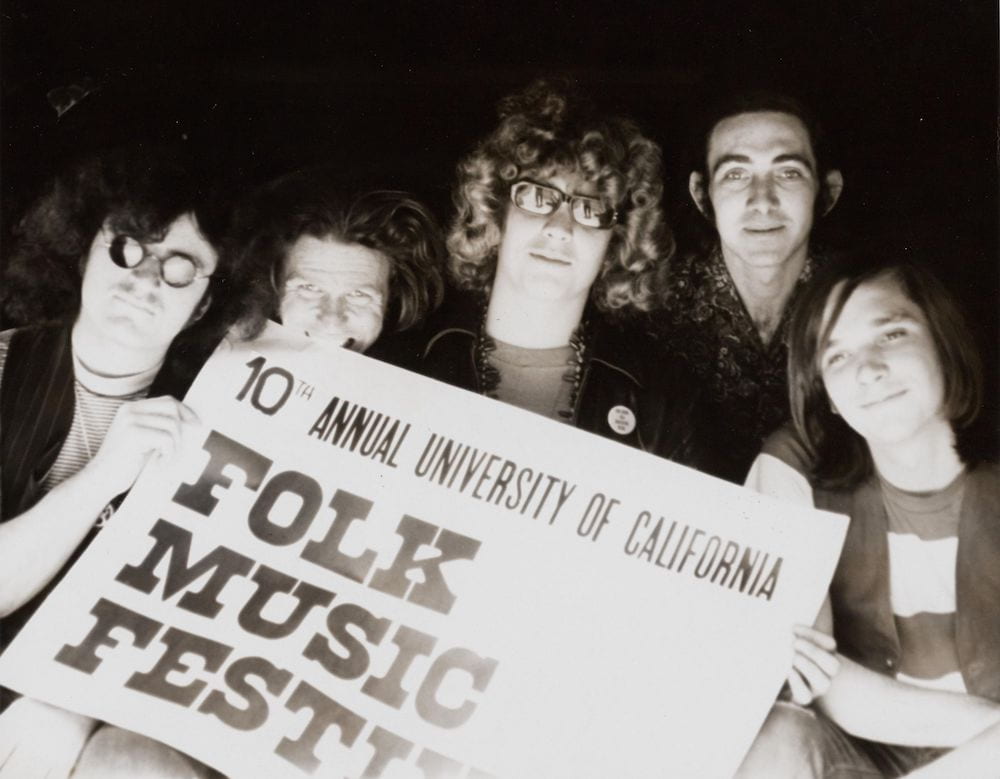

Country Joe and the Fish take a bite out of the upcoming 10th Annual University of California Folk Music Festival aka the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, spring 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

The 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival reflected Barry Olivier’s effort to link the event to countercultural trends vibrating out from San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood across the Bay and from around the world more broadly. Folk music’s definition and style were shifting rapidly, and Olivier hoped to manifest these changes at the Festival. “This is going to be a revolutionary year for us,” Olivier wrote to the pop music producer Phil Spector, whom he invited to speak at the Festival. “We’re attempting to break the structure way down, for a more relaxed feeling. …Additionally, we’re making an attempt to reach all the Bay Area rock musicians to invite them to attend one or several of the ticket events as our guests.”

1967

Trying to translate the more open, radical spirit of the emerging counterculture and Bay Area sound, Olivier brought together a fascinating range of performers to the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Younger singer-songwriters such as Janis Ian and Richie Havens were on the bill, as well as the electrified James Cotton Blues Band from Chicago and the Steve Miller Blues Band from San Francisco, the latter going on to score many rock hits in the 1970s after they dropped Blues from their name.

Building on the appearance by Jefferson Airplane in 1966, many emerging psychedelic rock bands with backgrounds in folk music appeared at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. The local folk-rockers Country Joe and the Fish had long been around the Berkeley folk scene. Now, with a commercial recording contract and growing fame on the emerging psychedelic dance concert scene in the Bay Area, they appeared at the Berkeley Festival. Crome Syrcus, based in Seattle, presented hard rock sounds combined with classical music. Robert Joffrey of the New York City Ballet had worked with Crome Syrcus on “Opus ’65,” a 26-piece orchestral score that would eventually become the ballet Astarte, which premiered in the Fall of 1967.

Red Crayola (later spelled Krayola) was an avant-garde art-rock trio from Houston, Texas. Like the Velvet Underground, the band experimented with electronic feedback, drones, and other challenging sounds quite distinct from traditional folk music fare.

Barry Olivier likely brought Red Crayola to the Festival on the recommendation of UCLA artist and conceptual theorist Kurt Von Meier (pictured below, and also joining the 1967 Festival as a guest scholar). Meier had begun writing excitedly about rock ‘n’ roll music as the folk music of the young. Later, in a 1969 article published in Art International Magazine, he would write about rock in tones reminiscent of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. Meier claimed that “the most significant cultural event of this century is the continuing revolution in all media of the arts that began during the mid-1950s” and that “rock and roll music was among the first, most immediate products of this cultural revolution.”

The group’s sets at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival were very controversial. During their loud, electrified performance in Pauley Ballroom one evening, the band put a microphone up to a melting piece of ice. The guitarist John Fahey joined them to improvise at another outdoor Festival performance. Usually Fahey only played acoustic, but on this occasion he seems to have possibly plugged in an electric guitar. At one point during the Sunday afternoon performance with Fahey, an announcer for KQED television, which recorded and broadcast that year’s proceedings, started talking over the performance, mistaking the music for an equipment malfunction.

The label Drag City released an album in 1998 that included a recording of Red Crayola’s performances at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. The recordings also have been posted to YouTube (we have been unable thus far to track down the video recorded by KQED, alas).

Some hated the music, comparing it to the sound of a dog dying, but others chanted “More! More!” when the band finished performing during one of their Festival sets. Serving on the Festival staff, Dev Singh relayed back to Barry Olivier that “somebody yelled aloud, quite audibly to the audience: ‘Barry Olivier is a punk!'” Singh also noted that there was “profuse booing” and that “someone(s) threw cabbage(s) onto the stage at the Crayola.” So far as Olivier was concerned this was all great. “Groovy!” he wrote on a note to himself, “Exactly what we wanted—a reaction!”

Not quite as dissonant and avant-garde, but still quite new for the Berkeley Folk Music Festival was Kaleidoscope, featuring a young David Lindley, who would go on to fame as a side musician to Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, and others; Chris Darrow, later of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band; and colorful characters such as Solomon Feldthouse and Chester Crill. The group performed a startling mix of old American folk songs such as “O Death” with references to the Vietnam War draft as they also added flourishes of Middle Eastern and Indian music to their acoustic-electric instrumentation.

A recording of Kaleidoscope’s performance at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival also exists on YouTube.

As Kaleidoscope’s performance suggests, the escalating US involvement in the Vietnam War haunted the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. In an article in the underground newspaper, Berkeley Barb, titled “Napalm Chills,” Hal Cohen noted how everyone from Kaleidoscope to Country Joe McDonald to Steve Miller mentioned Vietnam. Because the Festival took place over the July 4th weekend, the question of the war was particularly palpable. “Besides beautiful sound there was pressure in the air,” Cohen wrote. “We sit while a war goes on.” During Country Joe and the Fish’s set, the band’s leader remarked, “It’s the 4th of July and I’m very confused.” Steve Miller introduced his band’s final number by remarking, “The world is in terrible shape and we’re sitting here celebrating the 4th of July. So we’re going to play a positive statement.” Cohen made a point to note that the band performed a fierce, electrified instrumental song with no words of reassurance about whether the war in Vietnam was a patriotic venture.

As different and strange as the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival got, and as much as the contemporary politics of the Vietnam War hung over the proceedings, the Festival never completely abandoned its commitment to traditional American music. Doc Watson was back to pick and sing his Appalachian mountain music rags, blues, and ballads. Charley Marshall presented cowboy songs again. Fiddler Tony Thomas and 1930s string band musician Jimmy Tarlton traveled to Berkeley to perform. The incredible Reverend Gary Davis, the blind blues guitar virtuoso, traveled from New York City to appear at the Festival. He was one of the few performers to criticize Olivier, calling out the director from the stage for not returning Davis’s contract with punctuality. Olivier later straightened out the problem, and was generally celebrated as among the most conscientious of music producers.

Alongside them on the bill were younger musicians still interested in more acoustic, sometimes even quite ancient, folk sounds. Robin Goodfellow played traditional medieval British music. The Charles River Valley Boys played bluegrass from the banks of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Sandy and Jeanie Darlington performed old-timey duets and a few new, singer-songwriter compositions. Sandy would go on to write foundational pieces of rock criticism in local underground newspapers. Jeanie subsequently became a renowned traditional fiddler. Emerging from the local coffeehouse scene in Berkeley that also gave rise to Country Joe and the Fish, the local musicians in the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band brought the British skiffle sound to the West Coast too. Even as the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival expanded in “mind-blowing” psychedelic directions, it kept rooted in traditional sounds too.

Scholars at the event included Kurt Von Meier, who was much more of an avant-garde artist than a folklorist. Archie Green was back. Critic Ralph Gleason, jazz and pop music critic from the San Francisco Chronicle, joined them. Indicative of the shift away traditional notions of folklore, Olivier also invited pop music producer Phil Spector to the Berkeley Festival. Having met Spector a few months earlier at a Rock ‘n’ Roll Conference and Symposium at Mills College in Oakland, Olivier was keen to connect folk music to Spector’s smash hits made for AM radio. It remains a bit unclear if Spector actually showed up at the Festival that summer.

With such a daring mix of old and new, from ancient Elizabethan balladry to avant-garde performances of amplified icicles, rural fiddling and electrified blues-rock, the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival reveled in the Summer of Love energies surrounding it. While a reviewer in the Oakland Tribune asked, “Whatever happened to folk music?,” Olivier himself seemed to have come around to the position that everything was fair game. It was all folk music now.

Charles River Valley Boys, ca. 1967.

Arthel “Doc” Watson and his son Merle Watson, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Reverend Gary Davis at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Reverend Gary Davis, photographed in Berkeley in 1964. Photo: Robert Krones.

Robin Goodfellow, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Robin Goodfellow, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, ca. 1967. Photo likely by Barry Olivier.

Sandy and Jeanie Darlington, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Archie Green on the University of California, Berkeley campus.

Up against the wall, music critic! Ralph J. Gleason pretends to be arrested, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Ralph J Gleason, ca. 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Phil Spector at the Rock ‘n’ Roll Conference at Mills College, Oakland, March 1967. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Yet as pop music entered the picture, this would mean more challenges for the Berkeley Folk Music Festival as well. Events such as the Monterey International Pop Festival, held just south of Berkeley in June of 1967, or a few years later in December 1969 the violent, tragic Altamont Festival, made for a far more crowded field in local festival presentation (see the Other Festivals page for links to Barry Olivier’s photographs of these events, which he attended).

Expectations shifted as well. New, wilder styles of performance with loud music and light shows appeared at psychedelic ballrooms such as Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco. Instead of intimate gatherings at which performers and attendees sat around a campfire to sing with each other, now festivals became large-scale spectacles. They were meant to be immersive, Dionysian experiences not folksy get-togethers.

One sees the new energies in photographs of Sproul Plaza on the Cal campus during the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival (below). For Olivier, the challenge was to move in more “free” directions, as he had imagined in his conceptual plans for 1967, while retaining some of the spirit of the original Berkeley Folk Music Festivals.

Flute player in Sproul Plaza on the Cal campus during the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Freeform dancers on Cal’s Sproul Plaza during the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

More freeform dancing on Cal’s Sproul Plaza during the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Musicians performing on Cal’s Sproul Plaza during the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Another issue that began to emerge was politics. Back in the late 1950s, Barry Olivier had gotten in hot water at Cal for when he printed concert fliers and posters with a red background. The color was banned for its associations with communism. Now he faced the false idea that the Festival’s countercultural leanings were also anti-American. Because the 1967 Festival took place across the July 4th holiday, Olivier had designed a comical Uncle Sam playing an electric guitar for the print program (see below). With the era’s growing mood of distrust, a few older citizens of the Bay Area wrote to the University of California in protest: Olivier’s innocent Uncle Sam was an un-American graphical gesture, they claimed.

In the coming year, conflicts between the generations would only intensify around the US and across the world. Berkeley was an epicenter for these confrontations. Radical political activists clashed with conservative California governor Ronald Reagan. Young people flocked to the Bay Area in droves in search of hippie utopia. At the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival itself, Olivier and his staff would face the challenge of how to run a music event when riots broke out during protests just off campus on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue. Maybe turning back to a little tradition alongside the search for “far-out” freedom might not be such a bad thing during 1968.

1968

The year 1968 became known across the world as the “year of the barricades.” With the US intervention in the Vietnam War at its height, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in the spring, and later dramatic events such as the “police riots” at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, it was a time of protest, tumult, and upheaval. Berkeley remained a key site for radical activism, met with increasingly confrontational responses by California Governor Ronald Reagan. Taking place once again over the July 4th Independence Day weekend, the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival occurred while conflicts between police and activists raged on Telegraph Avenue, just down the hill from the Cal campus.

Yet Barry Olivier was able to pull off a very successful, peaceful event. Because he had grown up in Berkeley, he knew university administrators well. Some were even family friends with his parents. Those in charge of UC Berkeley trusted his ability to produce a successful event. At the same time, Olivier also had the respect of local activists and participants in the blossoming counterculture of the late 1960s. By offering free events alongside paid ones and communicating well with all parties, he eased tensions during the days of the 1968 Festival and was able to play a unique, mediating role in a fraught situation.

The 1968 Festival once again attracted large crowds over the course of its four days. Olivier drew back a bit from the rock music experiments of the previous year. “We put a great emphasis on the exploration of electronic rock music,” Olivier explained to Charles Seeger about the Festival in 1967, but “this year we are making plans for a Festival more along the lines of prior Festivals.” For 1968, the Berkeley Festival featured Joan Baez’s star power, the electric Chicago blues of Howlin’ Wolf, and the Bay Area psychedelic rock band Quicksilver Messenger Service. The more orchestral psychedelic rock band It’s a Beautiful Day performed as well. Alice Stuart returned, and was increasingly shifting from Joan Baez-style folk to a bluesier focus in her sound. John Fahey was back with his experimental acoustic guitar playing that merged classic blues and folk with extended, avant-garde composition and improvisation. Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach brought his ecstatic approach to Jewish liturgy back to the Festival. Of course, Sam Hinton held down the Master of Ceremonies role as he did every year.

Joan Baez, ca. 1968.

Joan Baez performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Jeff Lovelace.

Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett) Promotional Photo, ca. 1968.

Alice Stuart performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Sproul Plaza.

Sam Hinton performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Sproul Plaza.

A clipping from the Berkeley Citizen about John Fahey’s February 1967 performances at the Jabberwock, a key folk music coffeehouse in Berkeley.

Quicksilver Messenger Service, ca. 1968. Photo likely by Barry Olivier.

Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach and band performing on stage at the Hearst Greek Amphitheater during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert.

Olivier and his staff managed to handle the political protests in Berkeley during 1968, but just barely. A sign preserved in the Archive gives a sense of the mood at the time. “Telegraph is ours!” it declares in block letters, in a bid to take over the streets of the college town (see below). The tensions threatened the Berkeley Folk Music Festival proceedings just a few blocks away.

As Festival associate director John Chambless explained in a typed report, it was not easy. “Our festival has always been known for exceptionally good control and incidents in the past have been exceptionally few and minor.” For Chambless, “The prospect of violence, and my responsibility for it, with its subsequent influence on the future of our Festival, appalled me.”

Fortunately, he and Olivier had planned ahead for such a situation. During the so-called year of the barricades, they took theirs down. The large crowds coming over from Telegraph Avenue in search of free music were welcomed with open arms and festive participatory dance and music.

Enter Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. As Chambless wrote, Carlebach was “noted for his ability to bring about audience participation (in the form of singing and dancing). Therefore, Olivier and Chambless had him at the ready to “perform during our time of expected trouble.” The plan worked brilliantly. Carlebach took the stage, and while someone set off sporadic fireworks and there was a bit of an unruly spirit afoot, “the surge of new arrivals was quickly swept up in the general dancing.”

The crew for the festival was able to remove equipment, and the Festival proceeded, with subsequent admission-only events, peacefully and successfully. The documents below give a sense of how this all happened at the opening performance of the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

People dancing in Sproul Plaza, 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

People dancing in Sproul Plaza as Shlomo Carlebach performs on stage during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Dancers in Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Jeff Lovelace.

A sign from the protests on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

<

Fred Cody of Cody’s Bookstore on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, offers a “confidential report” on the protests in relation to the Berkeley Folk Music Festival in 1968.

Berkeley Folk Music Festival Associate Director John Chambless’s report about how the Festival handled the protests on Telegraph Avenue during the 1968 opening concert on Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley.

Steve Cain, “Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley: After the Barricades, Let the People Decide,” Ramparts, 24 August 1968.

Aside from the dramatic political events of the 1968 Berkeley Festival, the music was rich and varied. Jesse Fuller was back in one-man band mode, stomping on his “fodella” (a foot-pedal bass cello) and singing the “San Francisco Bay Blues.” David and Tina Meltzer presented brooding original songs with duet harmonies. Mayne Smith‘s connections to the Berkeley Folk Music Festival dated back to its earliest days. He returned now with an increasing interest in honky tonk and country music, which would be back in fashion in the hippie counterculture that year due to important albums such as the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Soon he would join forces with Mitch Greenhill, son of folk music manager Manny Greenhill, to form the country-rock band Frontier. Dave Frederickson, an anthropology professor at Sonoma State College and a stalwart of the Northern California folk scene, performed at the Festival. Paul Arnoldi played original songs with touches of flute accompaniment. The young African-American singer-songwriter Larry Diggs performed as well.

Dr. Humbead’s New Tranquility String Band played a driving version of old-time string band music. The group featured Jim Bamford, Mac Benford, and Sue Draheim, three of the finest musicians to emerge from the Colby House old-time music jam scene in Berkeley. Mike Seeger would eventually record them and others associated with Colby House for his cleverly named Berkeley Farms: Oldtime and Country Style Music of Berkeley album on the Folkways label (Berkeley Farms was a local milk company and Seeger used their logo for the album’s cover). Dr. Humbead was Earl Crabb, a local folk enthusiast who would go on to design Humbead’s Revised Map of the World with banjoist, instrument builder, and graphic artist Rick Shubb. Allan MacLeod, a disciple of Ewan MacColl, presented music of the British Isles. Vera Johnson traveled down from Vancouver to the Festival. Song of Earth Chorale traveled up from Los Angeles to present choral music from around the world. The local theater troupe the Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company brought the hippie quotient to the event with their mix of modern poetry and what Olivier described in the print program as “Oriental Dance Theatre.” Keeping with the hippie vibe, Bob Thomas and Will Spires‘s wonderfully weird Renaissance Faire-style band The Golden Toad made a surprise appearance. Comedy sketch radio stalwarts of the counterculture the Congress of Wonders performed as well, reflecting the broadened horizons of what counted as folk at a folk festival. Bringing things back to a more traditional sense of the music, folkorist Ed Kahn, an expert on fiddle tunes and international folk music, joined Charles Seeger as a resident scholar in 1968.

Dr Humbeads New Tranquility String Band, ca. 1968. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company, 1968. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Song of Earth Chorale performing in Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

The Andrews Sisters Gospel Singers performing at the Hearst Greek Amphitheater, 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert. Photo: Nicholas Kattchee.

Vera Johnson performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Allan MacLeod, ca. 1968.

Paul Arnoldi, ca. 1968. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Congress of Wonders performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Sproul Plaza.

We are fortunate to have audio recordings of the 1968 Berkeley Festival, made for broadcasting on KPFA-FM radio. One hears fireworks going off during the opening concert on Sproul Plaza, a reminder of the tense situation created by the protests on Telegraph Avenue, but overall the Festival sounds relaxed and peaceful, filled with wonderful performances by Jesse Fuller, Sam Hinton, local folk music television host Laura Weber, Tina and David Meltzer, Song of Earth Chorale, Dave Fredrickson, Dr. Humbead’s New Tranquility String Band and Medicine Show, The Golden Toad, Allan MacLeod, Vera Johnson, Larry Diggs with Mitch Greenhill, Alice Stuart Thomas (using her then-husband’s last name), Mayne Smith with Ray Bierl, Paul Arnoldi with Mitch Greenhill and Bob Sanderson, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, Andrews Gospel Singers of Berkeley, Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company, John Fahey, Howlin’ Wolf, and Joan Baez.

Listen to the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival on KPFA Radio

Photo: Shlomo Carlebach performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert on Sproul Plaza. Listen to the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival on KPFA Radio.

Also preserved is footage of a report on the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival by Ed Arnow for KPIX television news. It is preserved at the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archives at San Francisco State University. The report offers glimpses of the performers and general scene during the event. “They say that folk music is the music of the people,” Arnow notes, “and different people sure approach folk music differently. Here in the University of California’s lower plaza we sure have an assortment.” He interviews Mitch Greenhill, who remarks that the music he is making is “kind of strange don’t you think?” Similar remarks come from a guitar-banjo duo Arnow interviews. Sam Hinton presents some jaw harp and nose flute virtuosity. Allan MacLeod performs a traditional Scots ballad. Additionally, the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archives contain raw footage from KTVU of the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. This footage includes a bluegrass band that appears to be Vern and Ray, a campus plaza old-timey picking session among attendees, and a performance by the Song of Earth Chorale.

Watch television news footage of the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival, courtesy of the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archives at San Fransisco State University

Photo: Ed Arnow reports on the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival for KPIX television news. See the report as well as newsreel footage recorded by KTVU television news courtesy of the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archives at San Fransisco State University.

1969

The 1969 Berkeley Festival took place in the autumn rather than its typical time of early summer. This was a result of Barry Olivier’s involvement with an aborted Woodstock-like rock music and arts event planned for San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in August of 1969 known as the Wild West Festival (see the Other Festivals page for more about Wild West).

The Festival was toned down quite a bit. Most of all, it reflected a rapprochement between the traditionalists and the non-traditionalists in the broader folk scene. It also hinted at the shift underway in the folk revival as a whole. The focus on African-American and white Southern US folk music, which had accompanied the integrationist era of the civil rights movement in the early 60s, gave way to explorations of a broader range of vernacular ethnic styles. Perhaps this went along with political shifts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As identity politics emerged, so too did a more gloriously diverse folk revival.

Not one but two representatives of Cajun music appeared: the Opelousas Playboys and fiddle great Doug Kershaw. One of the most popular California bluegrass duos Vern and Ray, with young banjoist Herb Pederson, performed. Singing cowboy Charley Marshall was back. So were traditional-oriented singers Janet Smith and Alice Stuart. Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup debuted at Berkeley and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee returned to campus, having performed at Cal before, but never at the Berkeley Festival. Even two of the rock bands at Berkeley in 1969 were country-folk oriented: the Youngbloods and Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen.

Country Joe and the Fish appeared in the psychedelic rock slot. The band recited the obscene “Gimme an F!” chant in protest against the war in Vietnam while performing, as they had famously done at the Woodstock Festival a few months earlier, but it did not seem to stir up any major controversy. Once again the Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company presented their exotic, poetry-based theater. Mark LeVine offered his version of the folk-rock singer-songwriter genre. John Fahey was on the bill again, but proved too ill to perform.

While he wasn’t on the bill officially, Kris Kristofferson made an unannounced appearance at the Jubilee Concert for the 1969 Festival. With Harry Dean Stanton backing him, Kristofferson performed a well-received set.

As KCRA-TV reporter John Martin put it about the opening day concert of the Festival, it “seemed to confirm the very nature of folk music itself: nothing pretentious, just good solid feelings about real people and real life, some of it from a time long ago and some of it from a time not so far away at all.”

Brownie McGhee (guitar) and Sonny Terry (harmonica).

The Opelousas Playboys, ca. 1969.

The Opelousas Playboys, ca. 1969.

Doug Kershaw, ca. 1969.

Janet Smith, ca. 1969.

Vern and Ray (Vern Williams and Ray Park with Herb Pederson), 1965. Photo: Kelly Hart.

Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, ca. 1969.

Jesse Colin Young of the Youngbloods, ca. 1969. Photo: John Grissim.

Kris Kristofferson, ca. 1969. Photo: Jim Marshall.

Alice Stuart, ca 1969 or 1970. Photo: Barry Olivier.

John Fahey, 1966. Fahey performed again at the 1969 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. Photo: George Wilkinson.

1970

By 1970, Barry Olivier was exhausted. With a large family to support, continued financial instabilities, and the city of Berkeley increasingly riven by conflicts such as the People’s Park protests, he decided that this would be his last Festival.

Olivier also decided to adjust the numbering of the Festivals. He now included in his count the single-evening concerts he staged in 1956 and 1957, before the Berkeley Folk Music Festival was titled. He skipped the unlucky number 13. This made the 1970 event the fifteenth annual one.

As with the previous Festival in 1969, the event took place in fall rather than summer. Pete Seeger headlined the bill, along with the rhythm and blues singer Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. Joan Baez made a surprise appearance. Sam Hinton took up his usual role, as did Charles Seeger and Bess Lomax Hawes. Mimi Baez Fariña performed with her new musical partner Tom Jans. Malvina Reynolds was back, as were Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl. Earl Collins played traditional fiddle. “Mississippi” Sam Chatmon, who had been in the violin-and-fiddle country blues band the Mississippi Sheiks, traveled to Berkeley to perform. Radio personality Lee Boek, better known as Brother Lee Love, presented his improv theater with music. Sara Grey presented mountain music in the interpretive tradition of Jean Ritchie. Nick Gravenites performed solo and as the new frontman for the rock band Big Brother and the Holding Company once Janis Joplin left the group to go solo. The wondrously distinctive Robbie Basho took over the mystical guitar instrumentalist slot from John Fahey. Woody Guthrie’s one-time pal Ramblin’ Jack Elliott returned to the Berkeley Festival too. Having made an unannounced performance in 1959, he now officially appeared in the brochure for the 1970 Festival.

In 1970, the Berkeley Festival widened the folk lens to include more kinds of “ethnic” musical heritage. The People’s International Silver String Macedonian Band sang the “rich and intricate harmonies” of the Balkans with traditional instrumental accompaniment from that region of the world. The Na Rhma Wa Ci American Indian Dancers performed dance and music. The Mexican-American “Norteño” band Los Tigres Del Norte would go on to become internationally famous far beyond the folk circuit. In 1970, they were just beginning their musical careers.

Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Big Mama Thornton at the 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Na Rhma Wa Ci American Indian Dancers, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Los Tigres del Norte, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Malvina Reynolds, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Sam Chatmon, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

The final Berkeley Folk Music Festival previewed the rootsier turn among younger musicians in the 1970s. Mitch Greenhill and Mayne Smith joined forces in the honky-tonk country group Frontier. Shine and Co. was another local Bay Area band performing in a back-to-basics style. And longtime local folk musicians Toni Brown and Terry Garthwaite brought their amped-up country blues to the event with their group Joy of Cooking.

Sara Grey, promotional photo.

People’s International Silver String Macedonian Band, 1970. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Sam Hinton, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Workshop at the 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

John Shine. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Frontier. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Mimi Farina and Tom Jans publicity photo, ca. 1970.

Robbie Basho. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Bess Lomax Hawes, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Earl Collins, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Charles Seeger with Pete Seeger, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

Brother Lee Love, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Melville Bishop.

"This will leave something of a vacuum in the music world here"

When the Festival was over, Barry Olivier wrote to Jabberwock Coffeehouse owner Bill Ehlert in hopes that Ehlert might take over the event. “As you know,” Olivier explained, “I have just decided to leave the concert and festival management field, after 15 years of activity in Berkeley. It occurs to me that this will leave something of a vacuum in the music world here, and that it would be constructive and useful to find a successor who might take over my operation and continue some of the work I have begun, in addition to undertaking projects of his own.” Proud of his accomplishments, Olivier believed that the Festival had “become an internationally recognized and respected cultural event, and it should be continued as an important institution.”