1. Introduction: What Was the Berkeley Folk Music Festival?

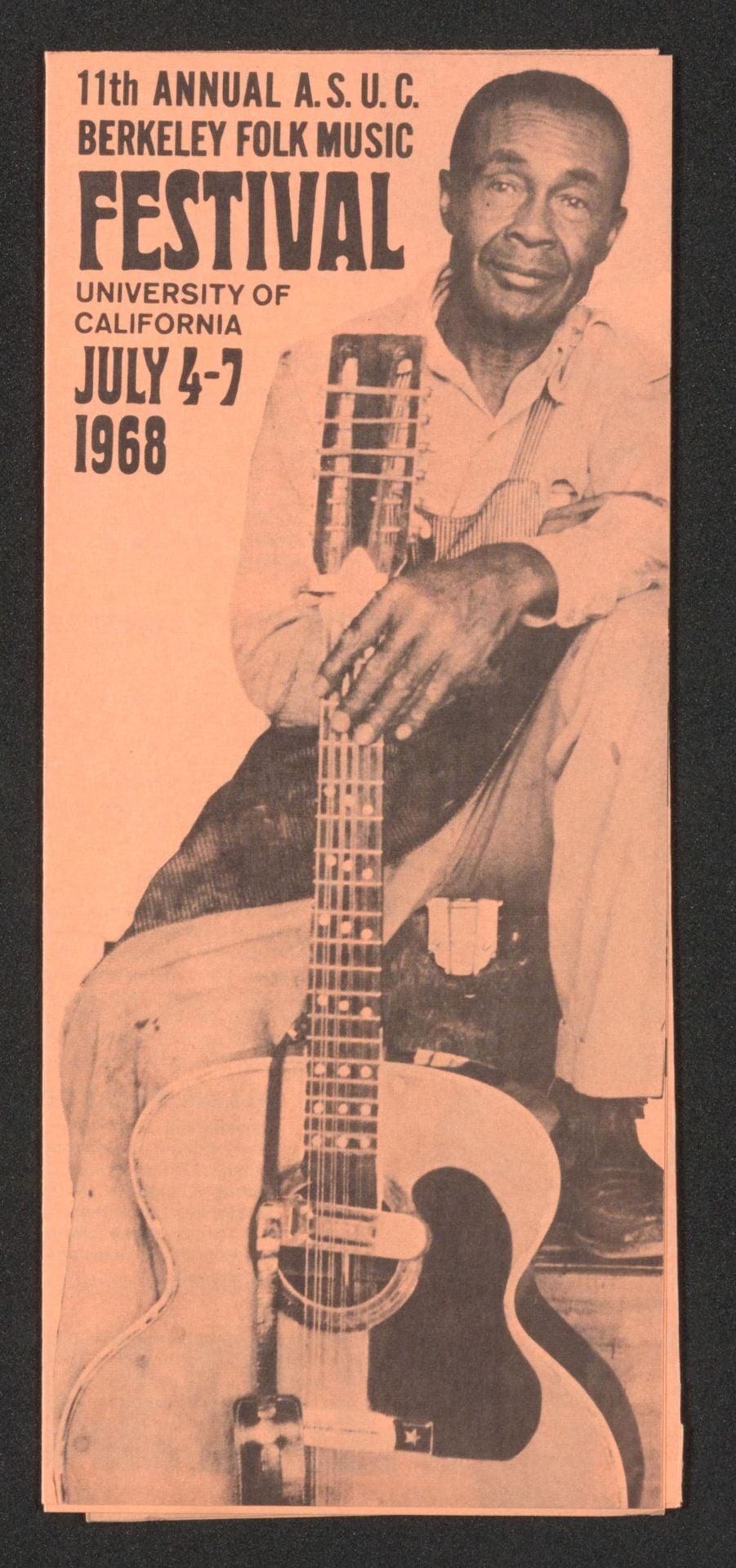

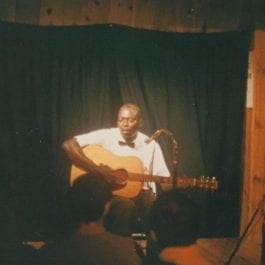

“Mississippi” John Hurt performs at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s closing Jubilee Concert, held in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater on the campus of the University of California. From 1958 to 1970, the Festival presented music, panels, workshops, and more to large audiences, with some of the biggest names in the folk revival performing in a casual, interactive setting at the preeminent public university in America.

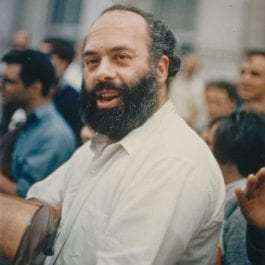

The Festival was Pete Seeger mesmerizing 6,000 people at the Greek Theater on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, with songs of his, Bob Dylan’s and others…. It was Blind Gary Davis chewing me out from the stage for not having returned his contract in time for him to have a copy before he left New York. It was the Red Crayola playing the strangest music I have ever heard, so loud that a third of the audience at the Pauley Ballroom left and the rest were none too pleased. …The Festival was Billy Faier, writing in a small New York folk music publication, following the 1958 Festival, that “Barry Olivier is the best promoter I know because he really loves the music.” And it is seeing the people whose lives and music have been influenced by the existence of the Festival….

— Barry Olivier, Berkeley Folk Music Festival Director, 1973

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival took place annually on the campus of the University of California in Berkeley between 1958 and 1970.

Those familiar with the folk revival’s history will notice that important performers—Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Bessie Jones, Arthel “Doc” Watson, “Mississippi” John Hurt, J.E. Mainer, Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, Los Tigres Del Norte, Jefferson Airplane, the Youngbloods, and Country Joe and the Fish, and many more—appeared at the event.

For those less familiar with the folk revival, the Berkeley Festival offers an entrance into crucial questions of culture and democracy in the United States during the decades after World War II:

- What did it mean to conceptualize music and culture as “folk”?

- Did this term only refer to music made non-commercially in rural or remote places or could it also be a term for music made in urban, modern, mass cultural settings?

- Did folk have a certain sound, or was it more about the process of how the music was made and received?

- What made the Bay Area and Northern California’s folk music scene distinctive?

- Conversely, how did the Berkeley Folk Music Festival fit in to the larger circuits of the national and international folk revival in the 1960s?

- The Festival took place during the height of the modern African-American civil rights movement in the United States. How did participants at the event reckon with issues of race and racial injustice in the domains of music and culture?

- What did it mean to hold a folk music festival at a prestigious research university such as the University of California?

- Did the Berkeley Festival make Cal a more inclusive, egalitarian place of knowledge and community, where musicians from the margins of society were treated as experts alongside those on the faculty at an elite postwar university?

- What did it mean to constitute festive public spaces of participation at an institution such as Cal, particularly during an era of protests by students?

- As the Free Speech Movement, anti-Vietnam War activism, and other uprisings and upheavals of the time period took place in the very same campus spaces as the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, how did culture and cultural heritage relate to politics and social movements of the time period?

- How did the sheer fun and joy of the Festival relate to its serious if imperfect efforts to represent American musical culture accurately?

Jean Ritchie and Sam Hinton pose on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, with a poster advertising the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

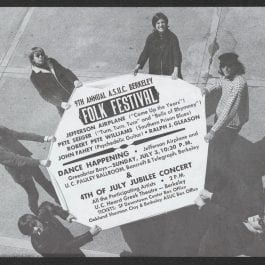

Members of the Jefferson Airplane advertise the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers at the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

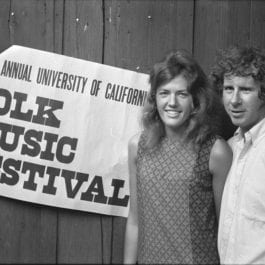

Sandy and Jeanie Darlington with Berkeley Folk Music Festival poster, ca. 1968.

Alice Stuart performing in the Hearst Greek Theater at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

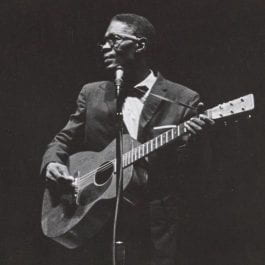

Mance Lipscomb performing at the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Sam Hinton performs in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers performing on stage in the Heart Greek Theater at the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert.

What's In the Digital Exhibit?

The digital exhibition introduces the story of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and its significance.

The digital exhibition introduces the story of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and its significance.

It features photographs and multimedia as well as a narrative of the Festival’s history, with sections about director Barry Olivier, the Festival’s early years in the 1950s and early 1960s, its little-studied but important role during the height of the folk revival, its transition years in the mid-1960s, and how the festival changed during the counterculture years of the late 1960s. The exhibition also examines the repository’s rich holdings concerning other festivals and the West Coast music scene more broadly.

We draw some conclusions about the Berkeley Festival’s place both within the folk revival and in US history as a whole during the decades after World War II.

Additional features include a timeline as well as an audio playlist of both audio recorded at the Festival and Spotify playlists of commercial recordings by artists who performed at the event. If you would like to have related music playing in the background while you peruse the exhibit, we recommend open the Spotify playlists in a separate browser window or the Spotify app.

Throughout the exhibition, you will find many photographs, documents, and audiovisual material. You can casually browse through the website as you might walk through rooms in a gallery exhibition or you can read the narrative text for more detail, contextualization, and interpretation. If you click on images, they will open up for closer inspection. You can zoom in on documents from the repository. Audio recordings and television footage are embedded in the exhibition as well.

You can also find out more about future directions of Dr. Michael J. Kramer’s Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project or click to the full digital repository, maintained by Northwestern University Libraries, to conduct your own research and exploration.

A Peek at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive is a rich trove of roughly 33,500 artifacts, including many never-before-published photographs. The repository also contains a small but wonderful set of audio recordings. Acquired by Northwestern University Library in 1973 from Festival director Barry Olivier, the Archive tells many stories, both big and small, about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and those who took part in it. It also sheds light on the folk music revival of the mid-twentieth century, particularly on the West Coast, which has not been studied as closely as folk music back East.

With its mix of educational panels, music workshops, and concerts, Berkeley paralleled more famous folk festivals, such as the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island, but it also forged its own style and feel. More casual than Newport and other folk festivals of the era, Berkeley encouraged mixing between audiences and performers within a scholarly context befitting of a university campus. Famous stars such as Pete Seeger and Joan Baez were as much Berkeley Festival attendees as celebrities at the top of the bill. There were numerous official yet informal events: coffee hours, barbecues, open-mic cabarets, barn dances, and campfires. Concerts took place in classrooms, quads, glades, ballrooms, plazas, and an amphitheater. The Festival cultivated an egalitarianism among participants.

The Festival went even further at times, proposing a rethinking of who had wisdom to offer in modern America and on what terms. Musicians who had seemingly been abandoned to history were suddenly highly valued for their abilities and perspectives. The Festival positioned them as teachers as worthy as any of the most prestigious faculty members at the university on which the event took place. Yet the Berkeley Festival did not merely romanticize older folk performers. Younger musicians were welcomed even if they made strange new sounds. At its best, Berkeley encouraged an immersive, democratic atmosphere that fit with the upswing in the radical search for new forms of freedom, equality, and community during the 1960s. While never dissolving into the political ferment of the time period—the Civil Rights Movement, the Free Speech Movement, anti-Vietnam War protests, or the hippie counterculture—the Festival was always in dialogue with these developments, feeding them and responding to them.

The Berkeley Festival also manifested an urge to reconnect with musical traditions while at the same time figuring out how folk music might speak to life in Atomic Age America. By the late 1950s, the Bay Area was at the cutting edge of new developments in post-World War II culture. The area featured emerging computer, aeronautics, engineering, and other industries connected to the Cold War military-industrial complex. The University of California-Berkeley was the official institutional leader of the nation’s nuclear research. In this context, the requirements of a postindustrial “knowledge” economy began to overshadow older agricultural and industrial modes of living and working. The region could sometimes seem to leap directly from fruit orchards and farmland to office parks, parking lots, and new suburban housing tracts. Waves of migration to the area by diverse populations during World War II also changed local demographics. California could seem a futuristic place by the 1960s. At the same time, conquest, war, exploitation, the crazed years of the Gold Rush, the vicious labor conditions of railroad expansion and consolidated agricultural production, and other historical legacies did not merely disappear. They lurked below celebrations of progress and prosperity. At the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, we see efforts to understand what cultural heritage was to be in this ruptured yet historically haunted context.

Berkeley quickly became a key node in the national—indeed international—folk revival, but the Festival also formed a crucial part of a robust West Coast music scene that has often been obscured by the East Coast folk revival story. The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive documents this thriving West Coast world, with its network of clubs, coffeehouses, music camps, folksong groups, and festivals in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Monterey, Fresno, Portland, Seattle, and elsewhere way out West.

Back at Berkeley itself, the Cal campus metamorphosized into a temporary but rich musical and cultural setting when the Festival took place. Banjos, fiddles, acoustic guitars, and harmonizing voices rang out. Eventually, electric guitars and drum kits joined the proceedings too. Thought-provoking workshops and panels posed fresh questions. Attendees mingled, listened, performed, interacted, debated, danced, enjoyed themselves, and shared in the making of the folk revival. Having fun, they also inevitably found themselves probing relationships between past and present, margin and center, inclusion and exclusion, memory and immediacy, and perhaps most of all, between tradition and modernity in a rapidly changing world.

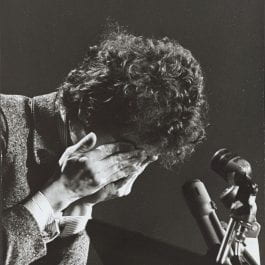

Bob Dylan at KQED News Conference, 3 December 1965. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Emma Ramsay and Bessie Jones of the Georgia Sea Island Singers. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Richie Havens at the 1967 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

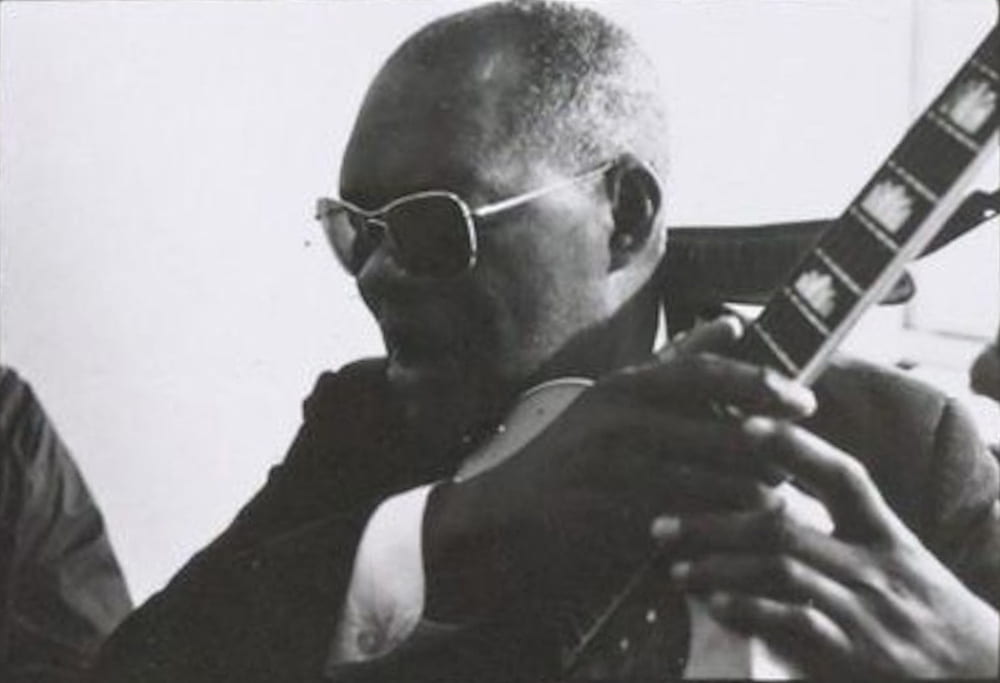

Samuel John “Lightnin'” Hopkins performing at the 1960 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Cliff Soubier.

Sam Hinton at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

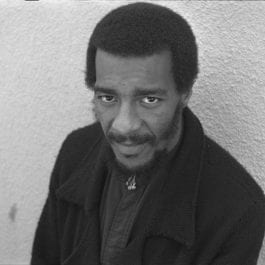

Daniel Moore, member of the Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company, 1968. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Jean Redpath and Jean Ritchie at a Berkeley Folk Music Festival Children’s Program, early 1960s.

Pete Seeger performing at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival in 1959 or 1963.

Jefferson Airplane performs at the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band, 1967.

Rev. Gary Davis, 18 January 1964. Photo: Robert R. Krones.

Los Tigres Del Norte performing at the 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

“Mississippi” John Hurt performing at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Faculty Glade. A child decided he had found the best seat (or under the seat) in the house.

Michael Cooney with Pete Seeger at the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Kelly Hart.

Na Rhma Wa Ci American Indian Dancers performing at the 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Juanita Montrand, guitar player and singer, in the early 1960s. Photo: Barry Olivier.

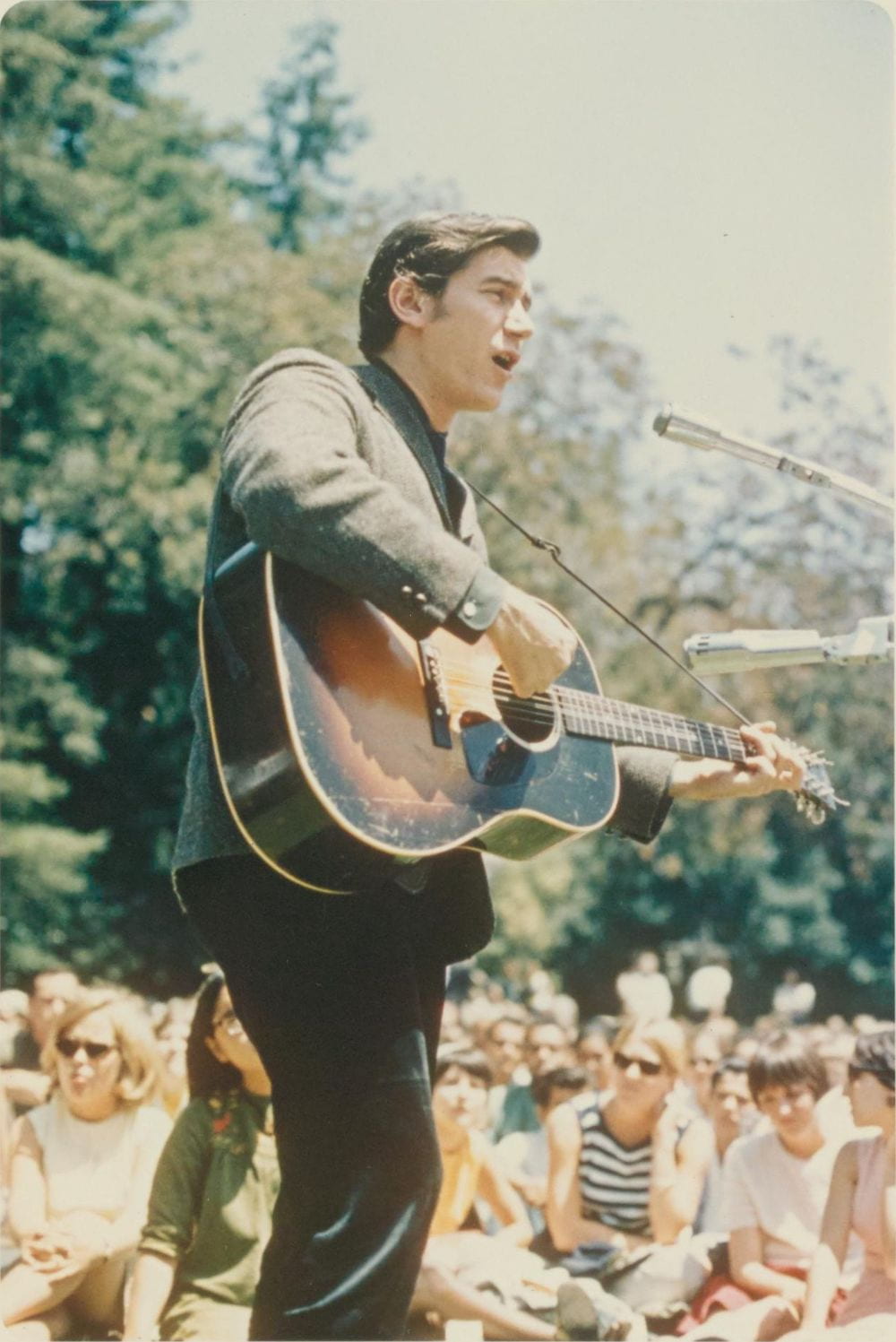

John Fogerty—"These Weren't Just Concerts: They Were An Education"

Among the many attendees at the early Berkeley Folk Music Festivals was a young John Fogerty, soon to be famous as the songwriter for and leader of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Fogerty attended with his mother, a folk music fan, and even took his first guitar lessons from Festival Director Barry Olivier.

The folk festivals on the campus at UC Berkeley were put on by a wonderful guitar teacher, Barry Olivier, who also gave me my first guitar lessons. I saw Pete Seeger, Jesse Fuller, Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sam Hinton, Alan Lomax—these weren’t just concerts: they were an education. I was enthralled by the whole thing. These folk festivals were hugely rewarding—just bedrock for me.

— John Fogerty, Creedence Clearwater Revival

Newspaper clippings and documents from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive indicate that Olivier kept close track of Fogerty’s career as it developed during the late 1960s with Creedence Clearwater Revival. The Festival Director even hoped to get his former guitar student’s band to perform at the event itself, but Fogerty’s management at the time rejected the offer.

Berkeley in Color

Jesse Fuller performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Sproul Plaza. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Song of Earth Chorale performing in Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

People dancing in Sproul Plaza as Shlomo Carlebach performs on stage during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Barry Olivier.

Shlomo Carlebach at the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: John Groper.

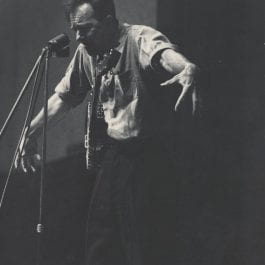

Phil Ochs performing in the Faculty Glade during the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening program.

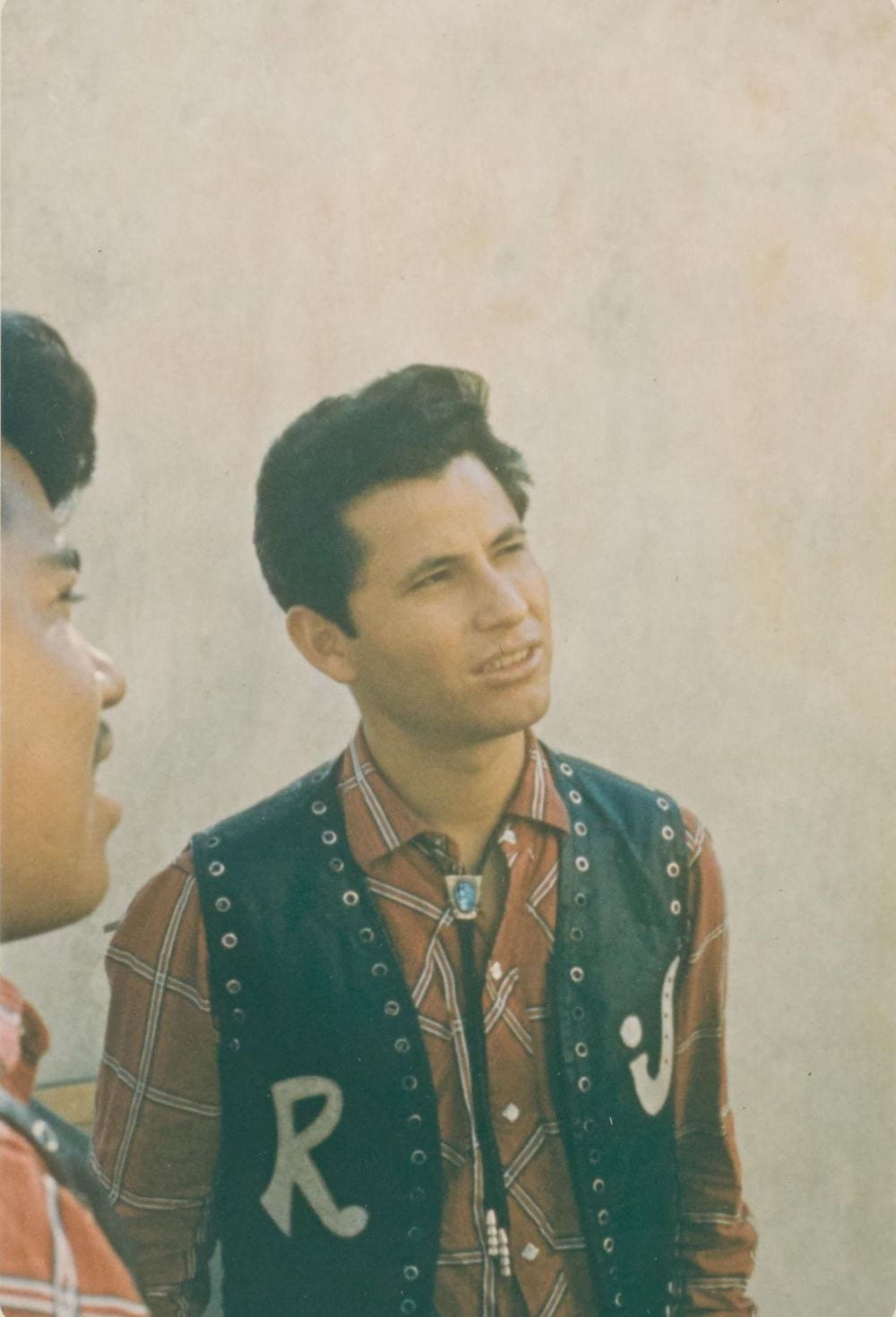

Los Halcones de Salitrillo backstage at the Greek Theatre during the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert. Photo: John Groper.

Robert Pete Williams at the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

The New Lost City Ramblers performing at the 1966 Berkeley Folk Music Festival opening concert in Faculty Glade.

Bess Lomax Hawes on stage at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, date unknown. Photo: John Groper.

Allan MacLeod singing and playing guitar in Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Musicians jamming in Sproul Plaza during the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Joan Baez performing at the 1968 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: Jeff Lovelace.

Who Played at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival?

Click on the names below to explore artifacts about each performer in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive’s digital repository. Each link will open a new browser window; return to this window to continue with the exhibit. Click on the button at the bottom of this page to continue with the exhibit’s narrative history.

Pete Seeger—Joan Baez—Arthel “Doc” Watson—“Mississippi” John Hurt—Samuel John “Lightnin’” Hopkins—Mance Lipscomb—Fred McDowell—Robert “Pete” Williams—Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee—Reverend Gary Davis—Jesse “Lone Cat” Fuller—Bessie Jones and the Georgia Island Sea Singers—New Lost City Ramblers—Mike Seeger—Cisco Houston—Los Tigres Del Norte—Los Halcones de Salitrillos—The Hackberry Ramblers—The Opelousas Playboys—Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett)—Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton—Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup—James Cotton Blues Band—Roscoe Holcomb—Almeda Riddle—Jimmie Driftwood (sometimes listed as Jimmy Driftwood)—Sam Hinton—Jean Ritchie—Jean Redpath—Janis Ian—Phil Ochs—Tom Paxton—Richie Havens—Ramblin’ Jack Elliott—Ewan MacColl—Peggy Seeger—Mimi Fariña—John Fahey—Robbie Basho—Larry Hanks—Dev Singh—Dr. Humbead’s New Tranquility String Band—Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach—The People’s International Silver String Macedonian Band—Song of Earth Chorale—Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company—Jefferson Airplane—The Youngbloods—Kaleidoscope—Red Crayola—Steve Miller Blues Band—Country Joe and the Fish—Big Brother and the Holding Company (post-Janis Joplin)—Commander Cody and His Planet Airmen—Joy of Cooking—Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band—Na Rhma Wa Ci American Indian Dancers—and many more.