How does an ancient mythical creature turn into a benchmark of American creativity? The year 2012 marked the 100th anniversary of Poetry magazine, Chicago’s internationally renowned poetry journal and the oldest monthly devoted to verse in the English-speaking world. Harriet Monroe founded the journal in 1912 after securing her start-up funds from 100 prominent Chicago businessmen, who each promised the support of fifty dollars a year for five years (roughly the equivalent of $1,500 today).

Monroe chose Pegasus, the winged horse associated with the Muses’ fountain on Mt. Helicon, as the magazine’s mascot. Over a hundred years, his transformations show more than just evolving magazine design–they track an elastic relationship between classical imagery and contemporary imagination, in American poetry as well as broader literary and artistic movements. Poetry’s Pegasus shifted shape according to the creative Zeitgeist throughout the twentieth century (read more about it here on the Poetry Foundation website) from Art Deco variations to James Thurber’s whimsical Pegasus, to even a complete exile from the magazine (1983-2003; the refutation and absence of classical imagery says just as much as its presence).

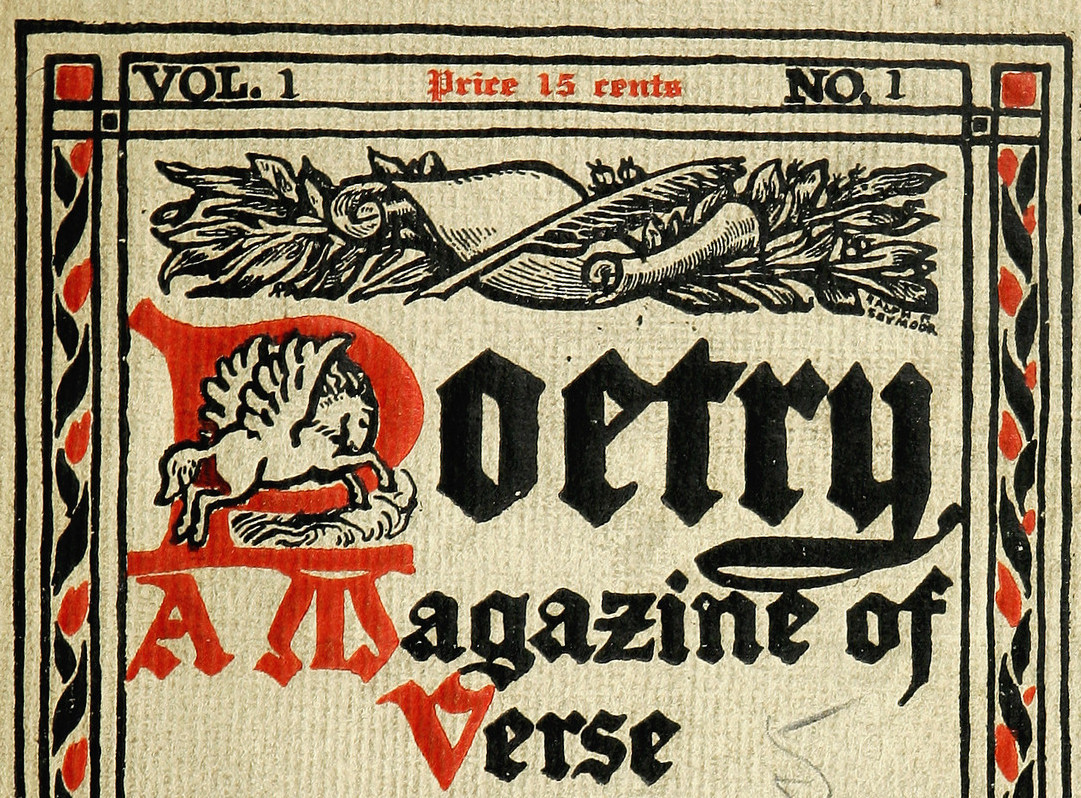

As part of the centennial celebration, the magazine invited eleven artists to interpret the magazine’s trademark image, a Pegasus in flight. The eleven versions appearing on each centennial cover resonate richly with the logo on the magazine’s first issues. Here we see Pegasus mid-gallop in the air of the capital P, as a symbol of poetry’s transcendent capacity to, as Monroe said, transport readers to imaginative heights of “human truth and beauty.”

Close-up of the first issue of Poetry

Contrast this Romantic view of Pegasus with Art Chantry’s creature, which, with characteristic postmodern flair, shows its seams. “I thought I’d go against the grain and do a ‘postmodern’ punk pegasus as a sort of contrast to the rest . . . I literally stapled this together and xeroxed it to make the image.”

December 2012 issue

Each Pegasus represents a distinct aesthetic, a different artistic moment. Ten years after Monroe invested Pegasus with ideals of “human truth and beauty,” she broadened the creature’s significance far beyond transcendental symbolism. Her 1922 Poetry essay on Marianne Moore presents the winged beast as a metaphor for a certain poetic weakness to soar towards bad poetry: “Miss Moore is in terror of her Pegasus: she knows of what sentimental excesses that unruly steed is capable.”

James Thurber’s Pegasus

Perhaps Monroe also considered Pegasus as a kind of sidekick to her heroic founding of the magazine—a creature that can adapt to and embody not only poetics, but also epic entrepreneurial endeavors. Monroe sensed it was time for a major design change in 1930, and asked English designer and lettering artist Eric Gill for a “highly stylized Pegasus in your best style which will carry us all off on his wings.” Her phrase “us all” resonates with her original mission statement: “The Open Door will be the policy of this magazine—may the great poet we are looking for never find it shut, or half-shut, against his ample genius!” Monroe’s editorial vision was democratic even as it made reference to what could have been seen as an elite classical discourse. The presence of Pegasus simultaneously characterized the magazine’s work as of the highest level of literary importance even as it delivered Pegasus out of an elitist realm. The marvelous hybrid finds a home in a magazine for “us all.”

Monroe was thrilled with Gill’s first Pegasus, debuting on the February 1932 issue, but her readers were not. They complained that not only were its ears and tail too like a donkey’s, but also that it “was a gelding instead of a stallion.” Gill reworked his image as requested, and his Pegasus redux appeared on the August 1932 issue, looking sleeker, faster, and—otherwise enhanced. Chicago print historian Paul Gehl: “Gill also added prominent testicles, perhaps his way of suggesting that Monroe and her readers were being a bit too literal about horsiness.” As an anatomically correct mythical horse, Gill’s second Pegasus belongs at once to both fantasy and realism, sharing these contradictory realms as many other classical figures would throughout twentieth century art. (K.H.)