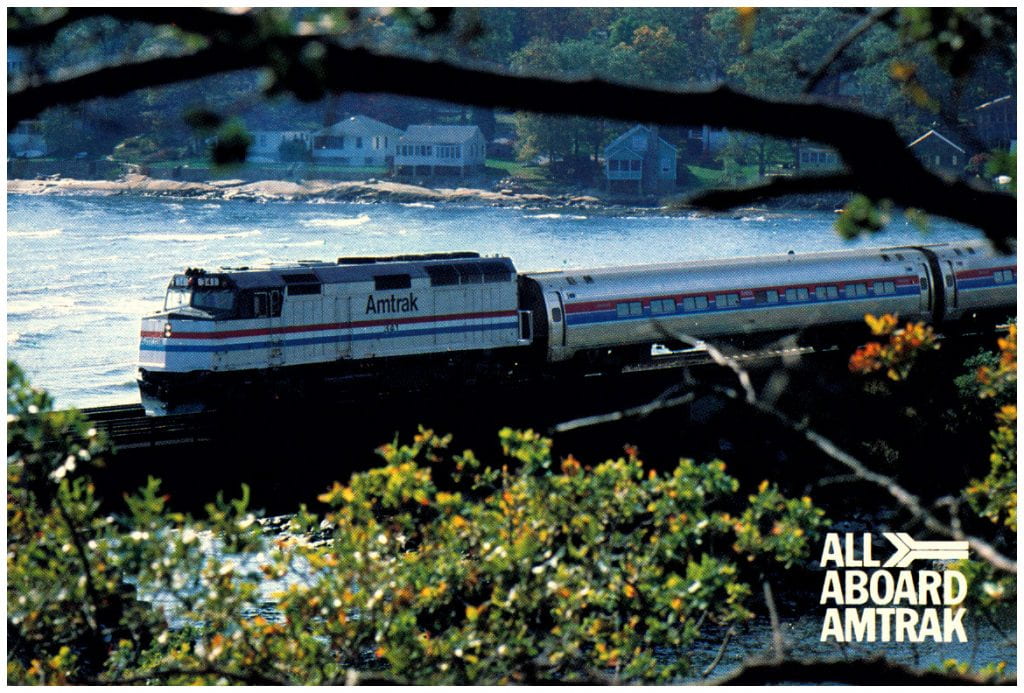

May 1, 1971 marked the beginning of Amtrak service. The intercity passenger rail market in the United States – which, at that point, was served by some two dozen privately-owned companies – was in rapid decline, with dwindling ridership numbers and deteriorating equipment and infrastructure. Amtrak was created with the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, consolidating and restructuring intercity passenger rail service under a quasi-public corporation in an effort to retain passenger rail as part of a balanced transportation system for the United States.

Fifty years later, there is increased interest in railroads, with large government investments in passenger rail proposed through an infrastructure package proposed by President Joe Biden, whose enthusiasm for the railroad earned him the nickname “Amtrak Joe,” and fueled by veteran railfans who have been active in the hobby for decades, as well as by young people – for many of whom the appeal of railroads stems as much from interests in sustainability, urbanism, and land use as it does from railroading itself.

In honor of Amtrak’s 50 anniversary, this exhibit looks back at highlights from the railroad’s history through passenger ephemera, reports, and other documents in the collections of Northwestern University’s Transportation Library.

Gary Gelzer Transportation Collection

Amtrak's Beginnings and the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970

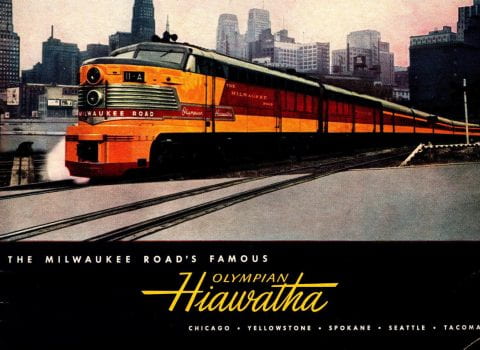

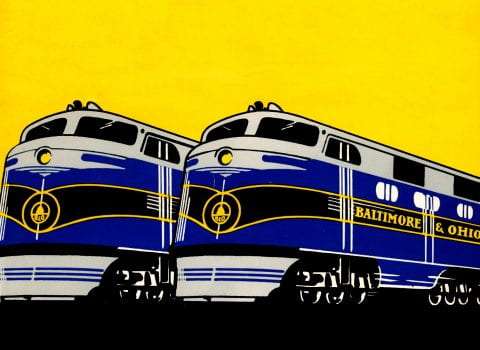

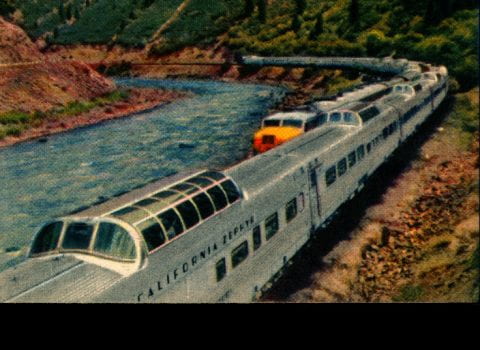

U.S. passenger rail service was once the primary mode of intercity travel in the United States, with 77% of passenger traffic carried on some 20,000 trains in 1929. The following decades saw a golden age of rail travel, with modern streamliner trains boasting luxurious accommodations, and five-course meal service served on white linen tablecloths in stylish dining cars.

Competition also rose during this period, in the form of bus travel, air travel, and the personal automobile. Government investments in the interstate highway system and the emerging aviation market helped promote the development of auto and air transport, and travelers took to the roads and the air in increasing numbers. Rail ridership went into sharp decline, and railroads sustained large losses from passenger travel.

By 1969, the number of trains still in service had declined to 450. In the years preceding the passage of the Rail Passenger Service Act, the railroads claimed losses of hundreds of millions of dollars per year on their passenger services.

With the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, Congress recognized that without action from the Federal Government, the passenger train, which it recognized as an essential mode of transportation, was in danger of disappearance. The passage of the act established a national rail passenger system which was joined by twenty of the twenty-six intercity passenger railroads in operation at the time. It also provided for the modernization of equipment, and authorized minimum standards for service.

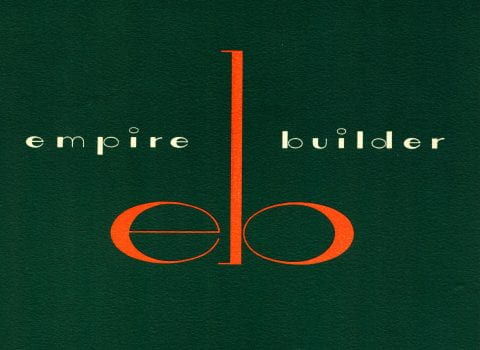

Predecessors of Select Routes

Many of the trains currently in operation today under Amtrak were inspired by named trains that were operated by earlier railroads. Click below to learn more about a selection of those routes.

National Railroad Passenger Corporation

In its initial conception, Amtrak was referred to as “Railpax,” which came from the telegraphers’ code for railroad passenger. The name Amtrak was announced publicly on April 19, a blending of the words “American” and “track.”

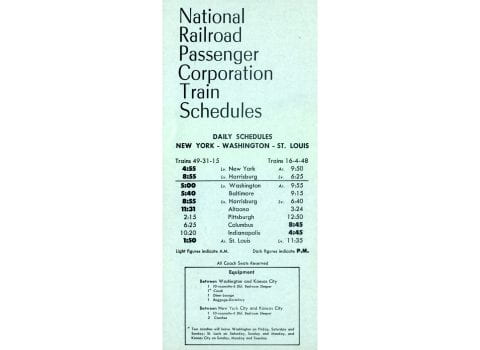

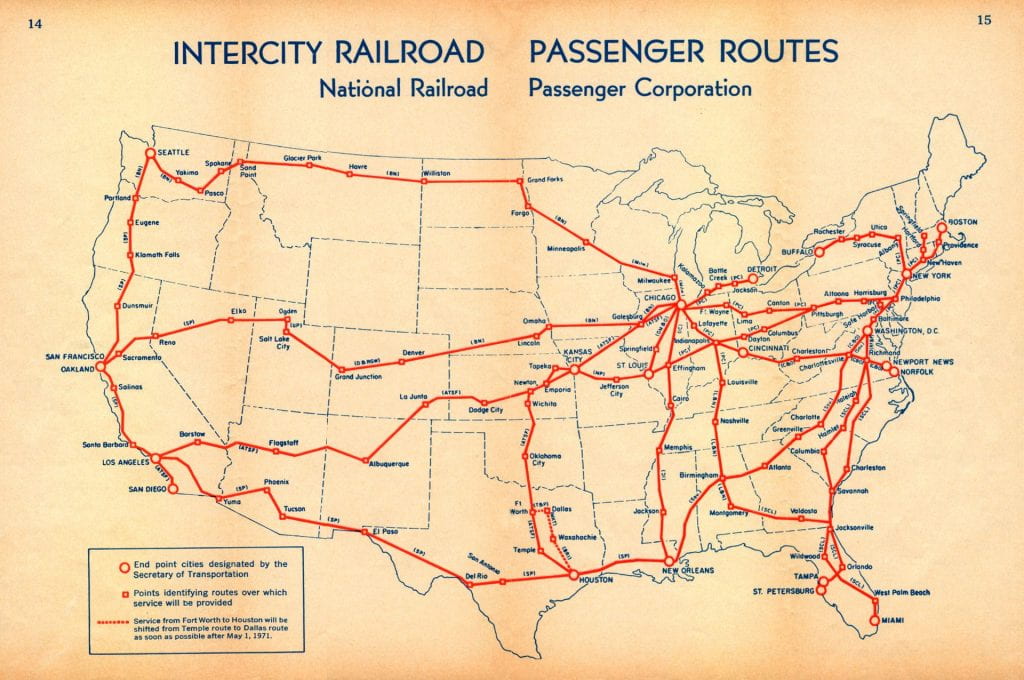

Some of the earliest timetables for service beginning May 1, 1971 are printed with the corporate name National Railroad Passenger Corporation. On this first day of Amtrak operations, the timetables shown here include service by the original railroads, operating under contract to Amtrak.

May 1, 1971: First Nationwide Schedule

Amtrak’s May 1, 1971 nationwide timetable was the first systemwide schedule of intercity passenger trains to be operated by the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. Printed inside was a message from Chairman of the Board David W. Kendall, addressed to the American traveler. Kendall represented the services on that first day of service as a large step towards the network of trains envisioned by Amtrak, a base upon which to expand the scope and quality of passenger rail service in the United States.

“We know these changes which are vital to upgrading rail service cannot be accomplished overnight. We are optimistic, however, that continuing improvements will attract hundreds of thousands of people who have not recently – or ever – relied on railroad transportation. We think the Amtrak system will become increasingly attractive to those who travel for business and pleasure, young people and older people, families and travel groups.”

John A. Swider Timetable Collection

"We're Making the Trains Worth Traveling Again."

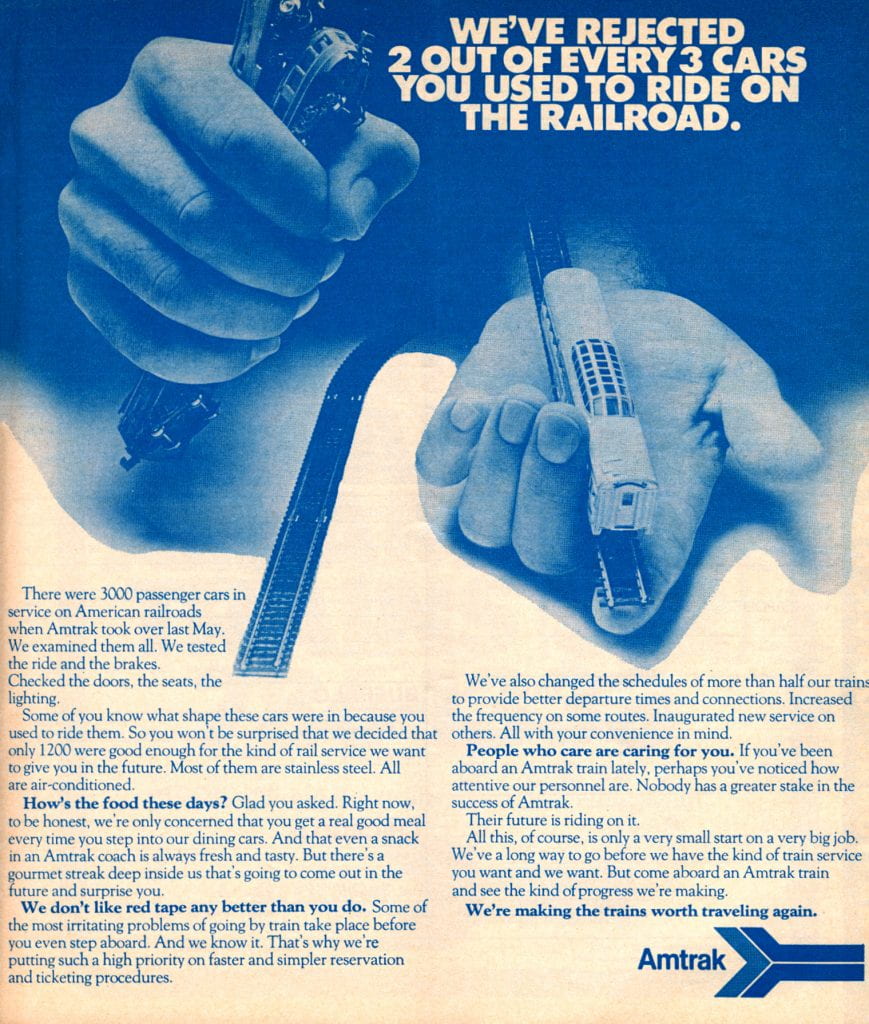

Echoing the messaging in the May 1 letter, Amtrak asked for the public’s patience as it worked on “Making the Trains Worth Traveling Again,” in the railroad’s first national advertising campaign, an example of which, from the Nov. 14, 1971 timetable, is shown at left below. The campaign highlighted the improvement of equipment and enhancements to the onboard dining experience, ticketing procedures, and reservation systems.

Amtrak’s January 16, 1972 timetable, at right, included a similar sentiment, with an emphasis on equipment: “You can’t run a good railroad without good railroad cars. So our first order of business was to take stock of our rolling stock. We examined all 3000 passenger cars formerly in service. And we’re keeping only the 1200 best, most of them stainless steel.”

John A. Swider Timetable Collection

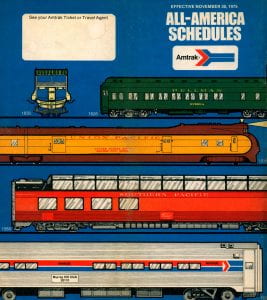

Equipment

The focus on equipment evident in the early timetables above is continued in the November 30, 1975 All-America Schedules pictured here. The cover is a mini-history of American railroads, dating back to 1830 with the Baltimore & Ohio’s Tom Thumb, the first steam engine built in the U.S. to operate on a railroad. The rail history continues with a 1926 Pullman passenger car, followed by the Union Pacific’s M-10000, an early streamliner that entered service in 1934; and the Southern Pacific’s Dome Lounge Car on the railroad’s Coast Daylight, known as “Stairway to the Stars” for 1955. The Amtrak car pictured at the bottom is an Amfleet first-class car, introduced in 1975.

John A. Swider Timetable Collection

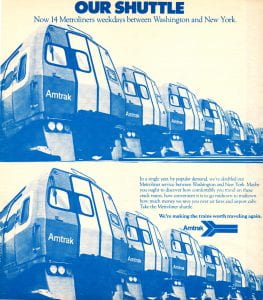

Metroliner

Metroliner service predates Amtrak, with origins in the prioritization of the development of high-speed rail authorized in the High Speed Ground Transportation Act of 1965.

The previous year, Japanese National Railways had introduced its Shinkansen, or “bullet train,” which was capable of speeds of 130 miles per hour. The Act was an attempt to encourage the creation of a high-speed rail system in the United States.

It established mandates for research & development, a demonstration program designed to measure the potentials and public response to high-speed trains, the creation of the Office of High-Speed Ground Transportation in the Department of Commerce, and $90 million over three years to put these programs into place.

First Tour of the New Budd 160 mph Train.

William R. Hough Collection

A prototype was already in development by the Budd Company, with plans for a 160-mph train that could compete with Japan’s Shinkansen. That train did not materialize, but Budd ultimately did develop the train that became the Metroliner, which entered service on Penn Central routes in 1969. Though it ran at up to 150 mph in testing, the Metroliner was limited by infrastructure conditions, and reached top speeds of 120 mph in revenue service. It was sometimes referred to as “higher-speed rail” – not quite high-speed. Powered by four 460-horsepower electric traction motors per car, the Metroliner completed the 226-mile route connecting New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. in less than 3 hours, or 2.5 hours in express service.

Metroliner service proved to be popular with the public and was increased under the operation of Amtrak; by the publication of the June 11, 1972 timetable shown below, service was doubled to fourteen Metroliners between New York and Washington daily.

John A. Swider Timetable Collection

Beginning in 2000, Metroliner service began to be replaced by Amtrak’s high-speed Acela Express and was phased out entirely in 2006.

Gary Gelzer Transportation Collection

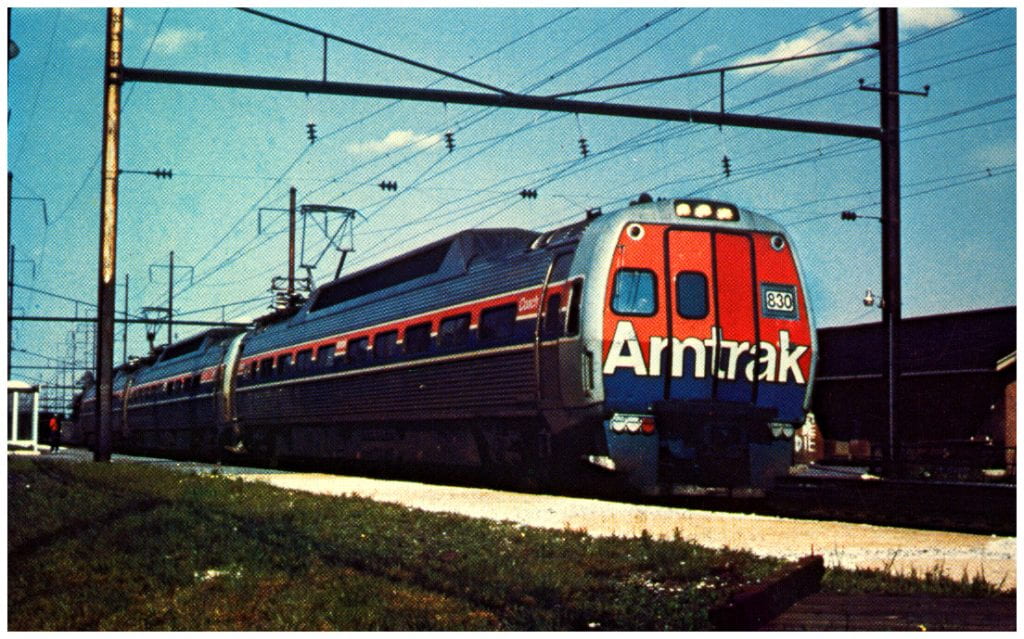

TurboTrain

Designed by United Aircraft Corporation and built at the Pullman Works in Chicago, the TurboTrain was powered by gas turbine engines similar to those found on jet aircraft. Coming online at the height of the jet age (Boeing’s 747 would enter service the following year), promotional materials and press coverage emphasized the Turbo’s similarities to jet aircraft, with headlines like, “”With Stewardesses, Films, Carpets, TurboTrain Is Jetliner on Wheels.”

Gary Gelzer Transportation Collection

TurboTrain entered passenger service on April 8, 1969, covering Penn Central’s 229-mile New York-to-Boston route in 3 hours and 39 minutes on one dally round-trip. Amtrak rolled the Turbo into its fleet when it took over railroad operations, and during the summer of 1971, the railroad co-sponsored a a monthlong cross-country tour of the new Turbo, together with the U.S. Department of Transportation. The tour was to be a test of the Turbo as well as a promotional tour, intended to “introduce modern trains to a younger generation of Americans that has never experienced them.” The train was met with large crowds along the route, and it was estimated that over 100,000 people viewed the train during that tour.

Tour of the Turbo, Summer 1971

Amtrak withdrew the TurboTrain from service in 1976, though Canadian National (and its successor, ViaRail), continued operations of its own Turbo sets until 1983.

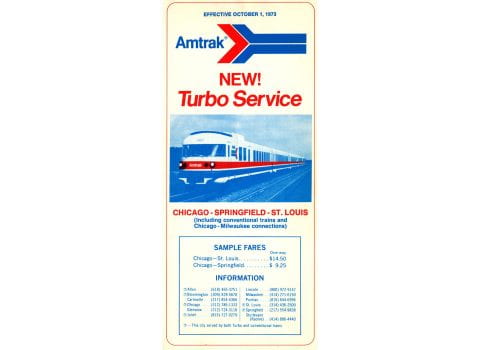

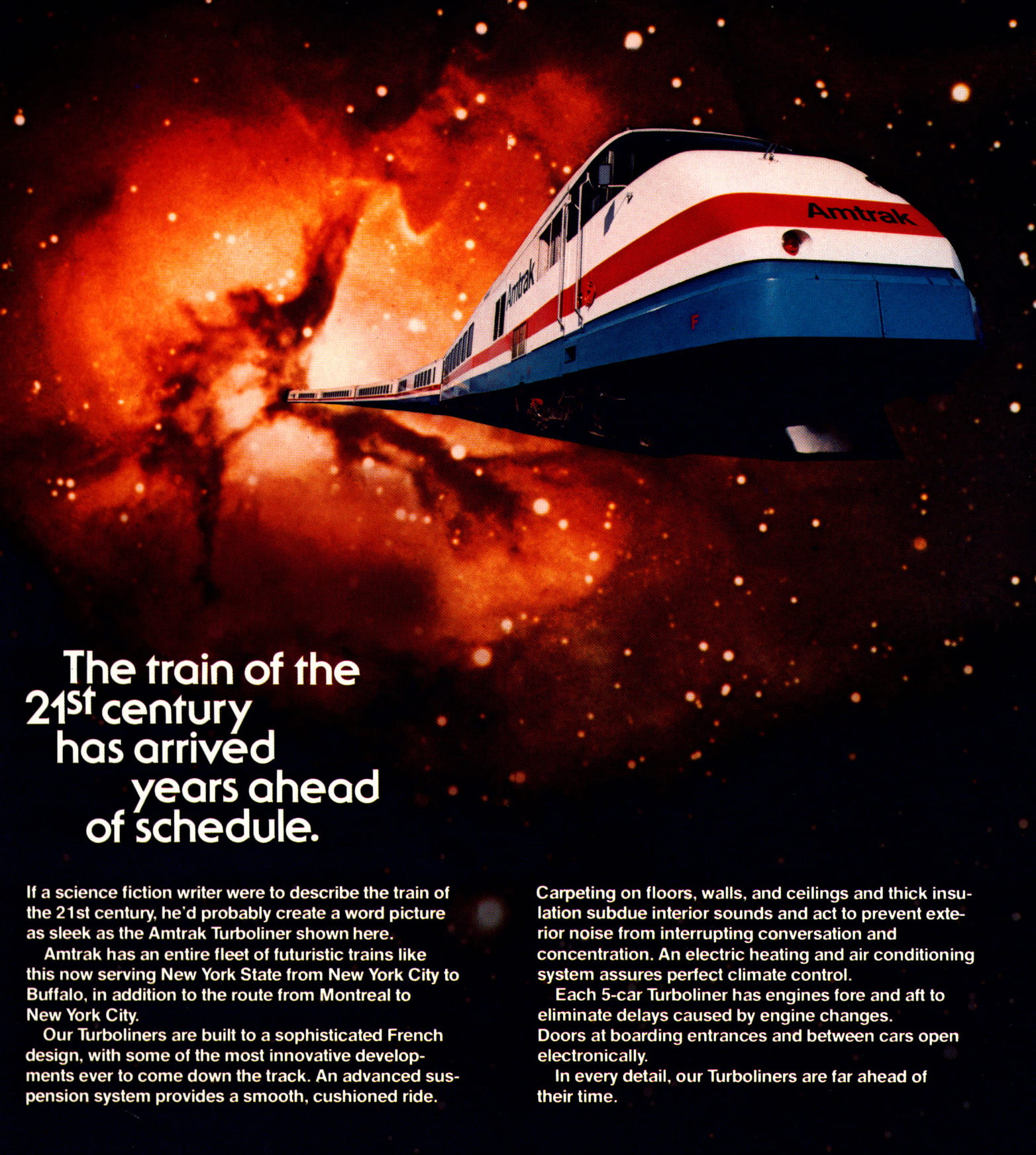

Turboliner: A Journey Into the Future

William R. Hough Collection

Turboliner entered service in 1973 and was among the first new equipment introduced by Amtrak. The 1977 pamphlet shown here invited travelers to join Amtrak on “a journey into the future,” promoting the “rocket-like profile” and futuristic design of the trainsets, as well as the high speeds achieved by the diesel-turbine engines: the Turboliner’s rated top speed was 125 mph. The French-built models that had been introduced in 1973, operating in the Midwest, were supplemented by American-built models produced by Rohr Industries in 1976, and Turboliner service was expanded to the Northeast. The Turboliner remained in use for nearly three decades until being retired in 2003.

Superliner

Amtrak’s Superliner was introduced into service in 1979, billed as “the first new long-distance train in two decades.” The October 28, 1979 national timetable shown at left is the first to show long-distance schedules for the Superliner, which entered long-distance service on that date on the Empire Builder route. A Superliner coach is featured on the cover of that timetable, along with dates that Amtrak’s earlier equipment was introduced: the Metroliner in 1969, pre-Amtrak; the French Turboliner in 1974; Amfleet in 1975; and the Rhor Turboliner in 1976.

The design of the new double-decker cars was influenced by the popular Hi-Level cars that had been in use by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, and which were absorbed by Amtrak when it assumed operations in 1971.

Amtrak promoted the train’s comfort, roominess, and the exceptional views afforded to passengers. Other amenities on the Superliner included a lower-level piano lounge and an upper-level “penthouse on wheels” with luxurious seats, beverage service, and large vista-windows. A range of passenger accommodations included family, economy, deluxe, and special bedrooms, designed to accommodate passengers with disabilities.

William R. Hough Collection

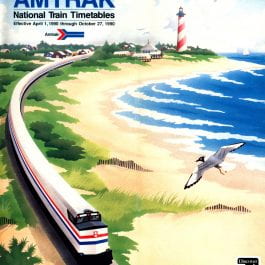

1980s/1990s Cover Series

A series of timetables from the late 1980s through early 1990s celebrated the range of Amtrak’s network through a series of cover art by illustrator Nathan Davies of the E. James White Design Company. Amtrak’s services covered cities, farmland, mountain and desert vistas: the entirety of the nation. On an Amtrak train, passengers could visit distant destinations – but even better, all of the beauty of the country was right outside the car window. The timetables below are from the William R. Hough and John A. Swider Collections.

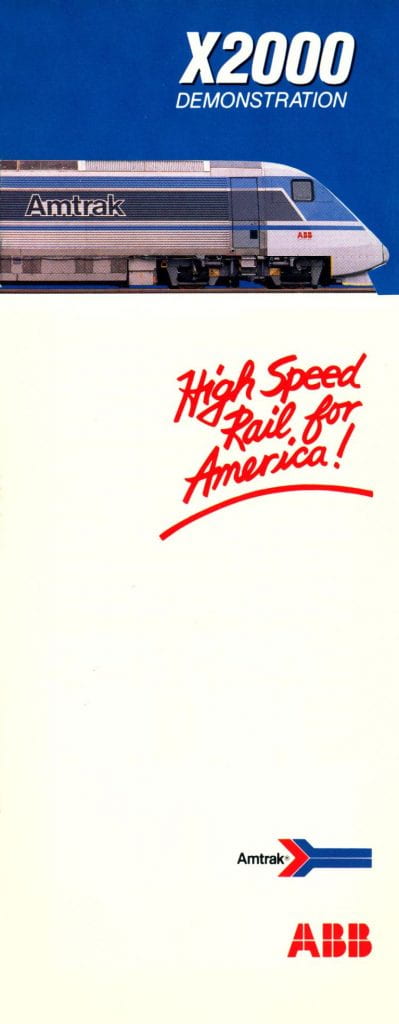

High Speed Rail for America! The X2000

Efforts to introduce high-speed rail to the United States continued through a demonstration in 1992-1993 that included the X2000, manufactured by ABB and leased from the Swedish State Railway. The X2000 was billed as “The Most Economical High-Speed Train Concept Ever Developed,” as it ran on existing main line rail and required low infrastructure investments.

Efforts to introduce high-speed rail to the United States continued through a demonstration in 1992-1993 that included the X2000, manufactured by ABB and leased from the Swedish State Railway. The X2000 was billed as “The Most Economical High-Speed Train Concept Ever Developed,” as it ran on existing main line rail and required low infrastructure investments.

The X2000 operated in revenue service on existing Metroliner routes, running at speeds of up to 155 miles per hour, and toured the United States on a national tour later in 1993.

Following the demonstration of the X2000, Amtrak partnered with Bombardier and GEC Alstrom to develop a high-speed train for the United States – the train that would become Acela.

All materials in this section are from the William R. Hough Collection.

Acela

In development and before it was branded as Acela (a blending of the words “acceleration” and “excellence”), Acela was known as The American Flyer. The American Flyer branding is shown in promotional materials published by manufacturer Bombardier which, together with GEC Alstrom, developed the Acela to serve Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor following demonstrations of European high-speed trains X2000 and ICE 1.

The first Acela Express entered service Dec. 11, 2000 with service between Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and points in between at speeds of up to 150 miles per hour. Ridership and revenues in the Northeast Corridor, where the train was introduced, increased dramatically with the higher-speed trains, which are in operation twenty-one years later.

Plans are currently underway to retire all existing Acela trains from service by 2022, to be replaced by Avelia Liberty. Produced by European manufacturer Alstom (formerly GEC Alsthom), the Avelia is expected to bring increased passenger capacity, speeds of up to 186 miles per hour, and improvements in safety and comfort for riders.

All materials in this section are from the William R. Hough Collection.

Sidetracks

A Journey into the Future of Amtrak

The American Jobs Plan, the infrastructure bill proposed in March 2021, includes $80 billion to improve Amtrak service. This includes infrastructure improvements such as the replacement or repair of tunnels and bridges – many of which, in the Northeast Corridor, are over a century old – as well as expansion of the network with new rail lines, the addition of routes, and increased services on those routes.

Amtrak CEO Bill Flynn addressed the bill: “President Biden’s infrastructure plan is what this nation has been waiting for. Amtrak must rebuild and improve the Northeast Corridor and our National Network and expand our service to more of America. The NEC’s many major tunnels and bridges – most of which are over a century old – must be replaced and upgraded to avoid devastating consequences for our transportation network and the country. In addition, Amtrak has a bold vision to bring energy-efficient, world-class intercity rail service to up to 160 new communities across the nation, as we also invest in our fleet and stations across the U.S. With this federal investment, Amtrak will create jobs and improve equity across cities, regions, and the entire country – and we are ready to deliver. America needs a rail network that offers frequent, reliable, sustainable and equitable train service. Now is our time, let’s make rail the solution.”

Gary Gelzer Transportation Collection

Cheers to 50 years of Amtrak.

Rights

Northwestern University Libraries is dedicated to the fair and ethical preservation, digitization, curation, and use of its collections. This exhibit is made available to the public under Fair Use (Section 107 of the Copyright Act) for learning and teaching purposes, as well as to promote the mission and activities of Northwestern University Libraries (ARL Code of Best Practices in Fair Use). Northwestern University Libraries does not claim the copyright of any materials in this collection. If you are the copyright holder of any item(s) in this collection or have questions, comments or concerns about this exhibit, please contact us via email at transportationlibrary@northwestern.edu.

More Information

Items in the exhibit are housed at Northwestern University’s Transportation Library. Email transportationlibrary@northwestern.edu with questions, or to schedule an appointment.