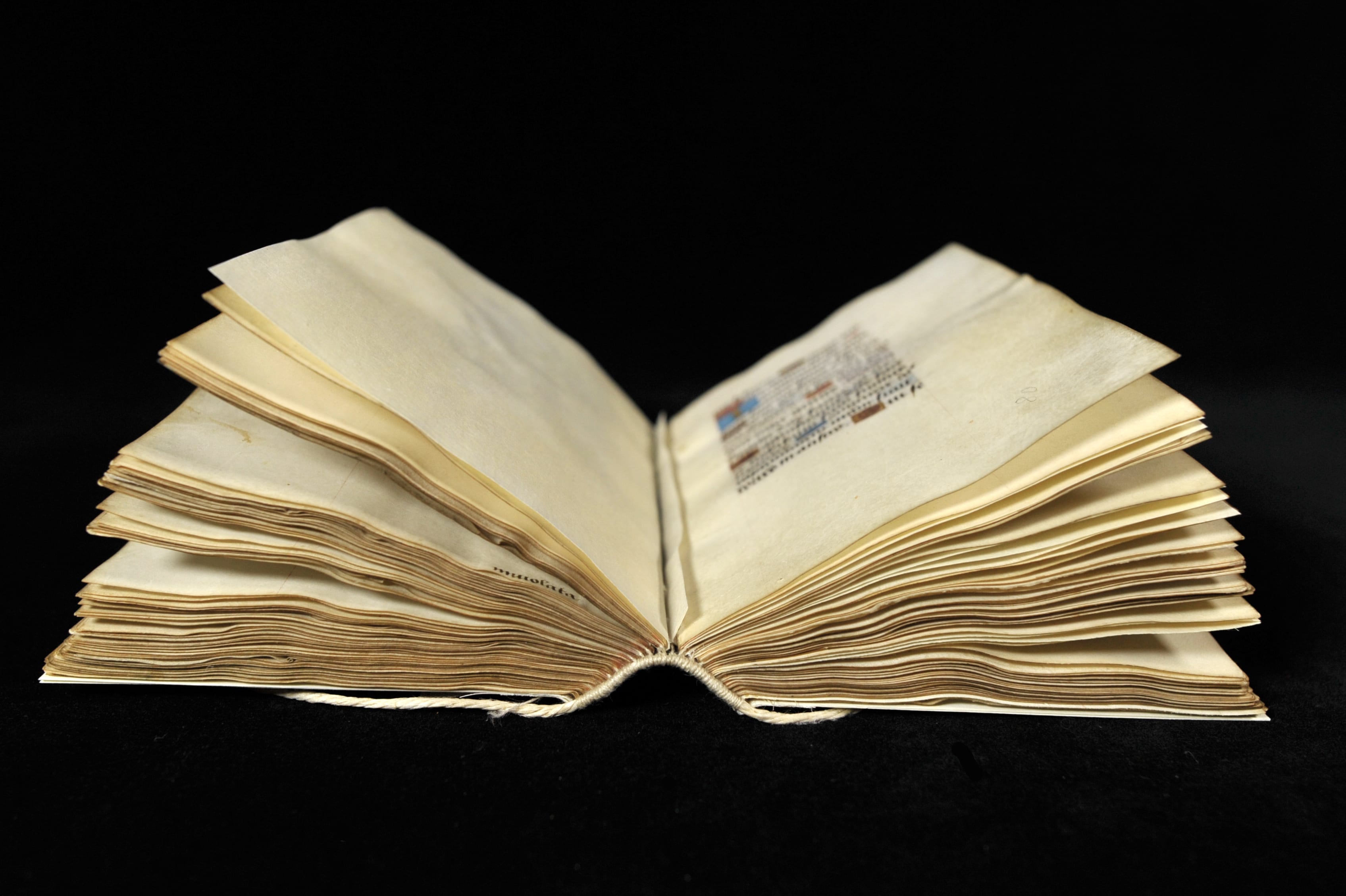

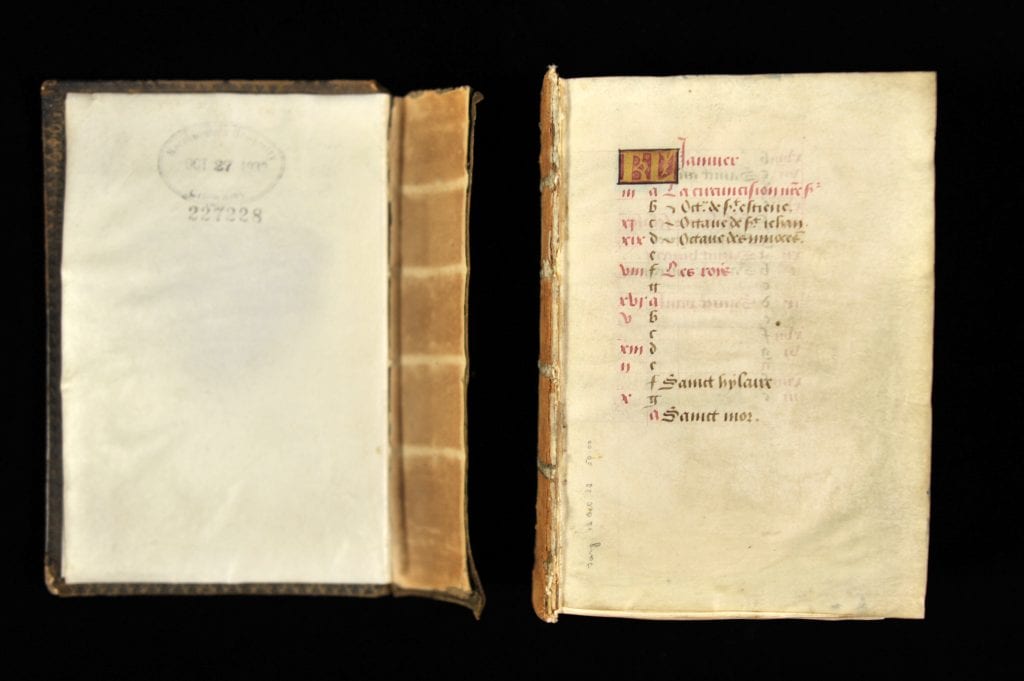

Last year, this 15th-century book of hours came down to the Northwestern Libraries conservation lab for rebinding. The manuscript had previously been rebound at some point in the 19th century. This “new” binding had fallen into disrepair, with both boards detached and several breaks in the sewing.

Rebinding a historical book is not a decision to be made lightly. In our job as conservators, we try to stabilize cultural heritage materials while imparting as little change as possible to avoid damaging historical evidence. But in a case like this, where the binding on a book is not only degraded, but unoriginal and inappropriate, we may take the opportunity to recontextualize the object with a new, historically sympathetic binding.

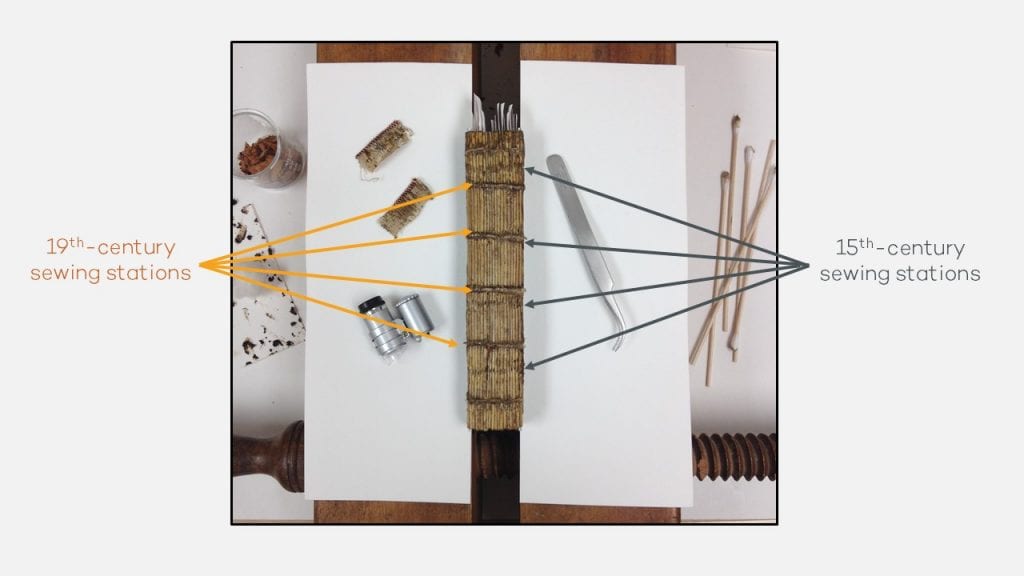

After the manuscript’s spine was cleaned of its lining and adhesive, the original sewing stations were revealed. The 19th-century binder had moved the sewing from the even spread typical of Gothic-era binding towards the more concentrated layout popular in the 19th century.

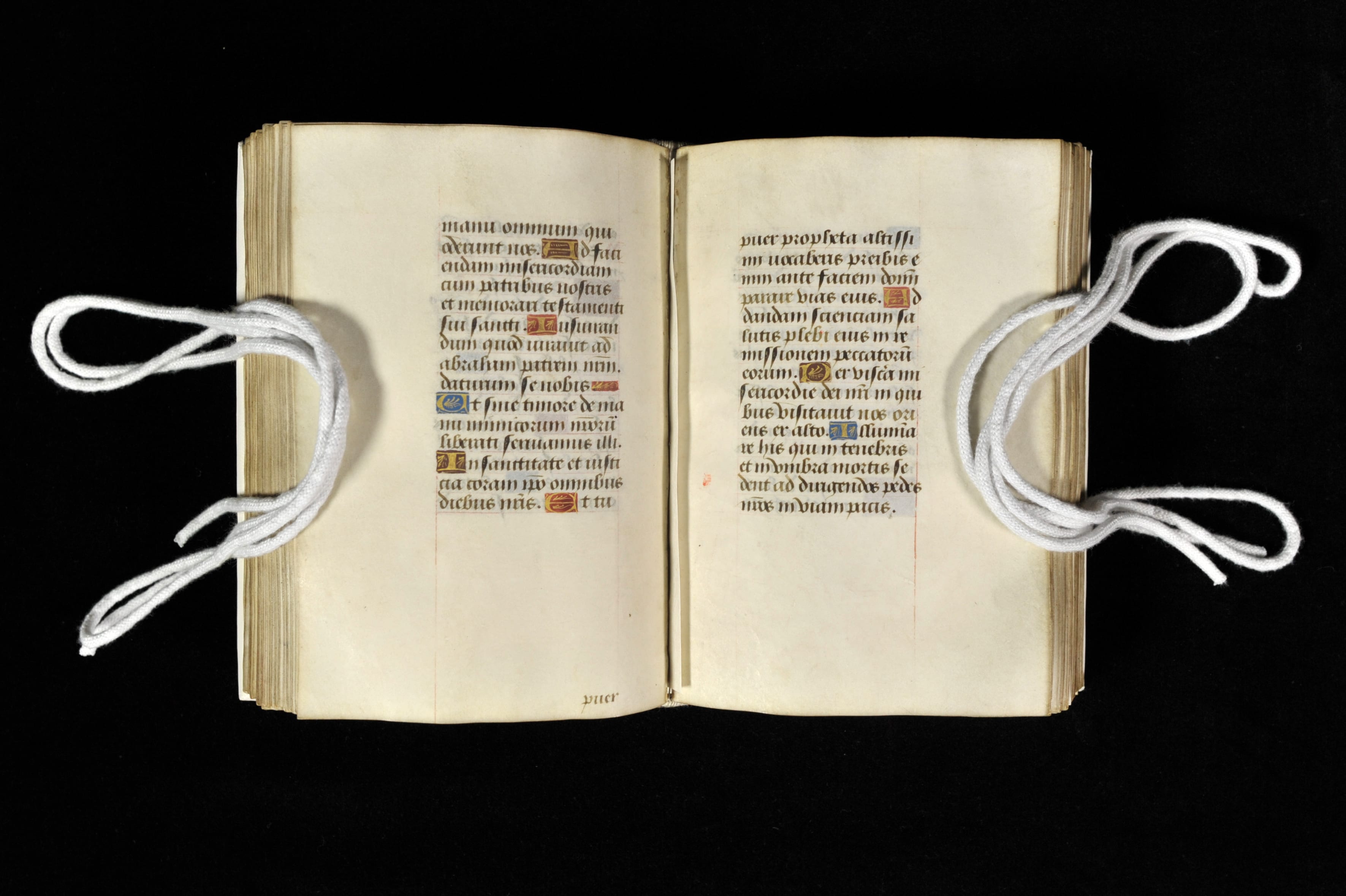

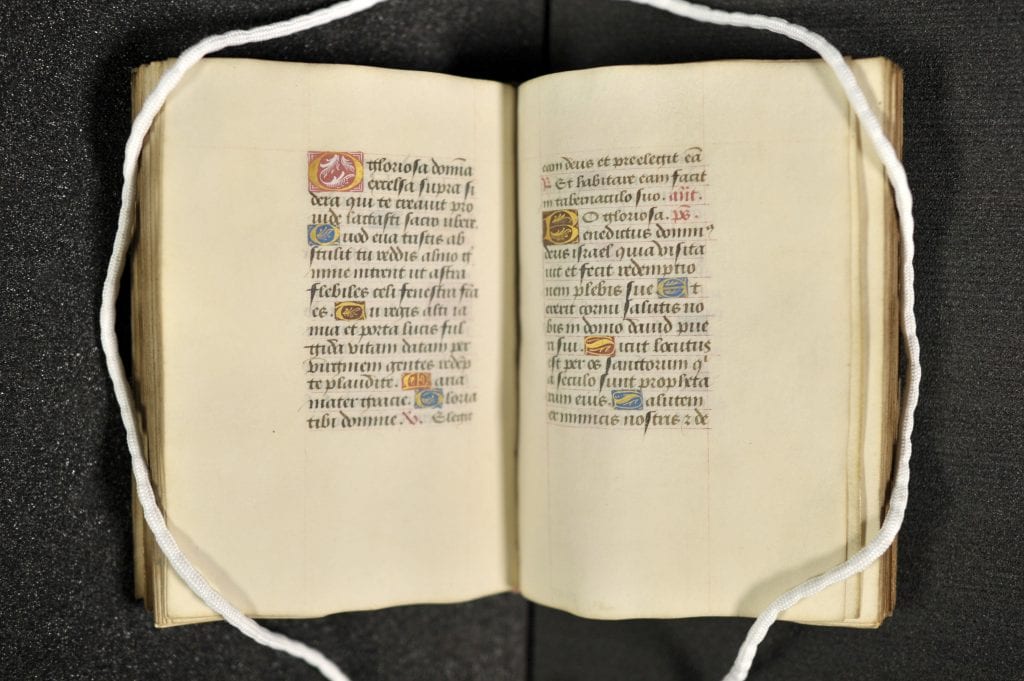

The manuscript’s media (the inks and paints) had degraded, as well. Over the centuries, the binding agents holding the pigments to the parchment surface become brittle, and there is an increased risk for losses to the text. The first few pages had already lost a significant amount of media. Media consolidation was performed on much of the manuscript to prevent further loss. This process was done using a dilute gelatin solution. The gelatin was brush-applied under microscope in areas with flaking media, and applied with an aerosol generator in the more friable areas.

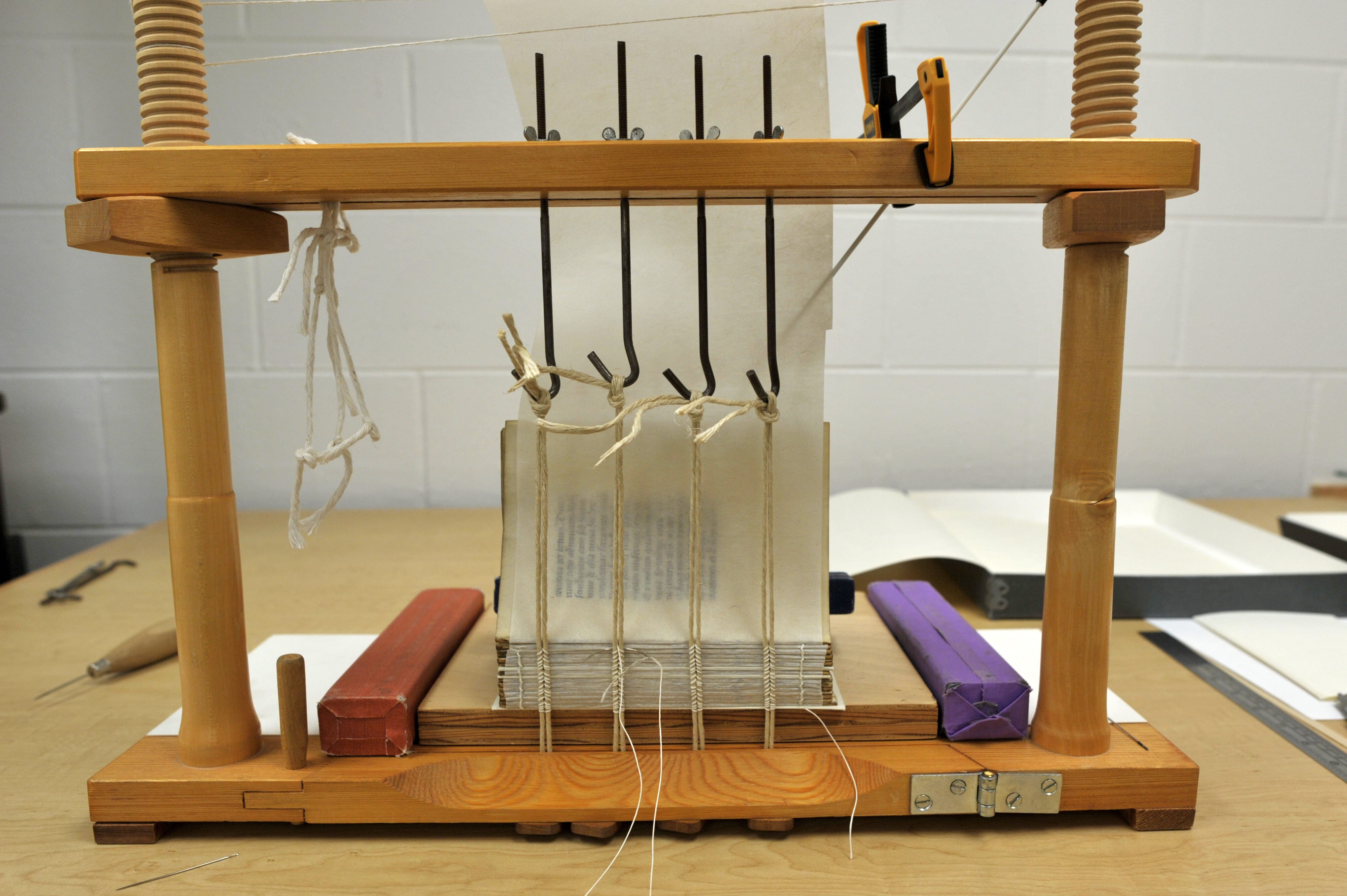

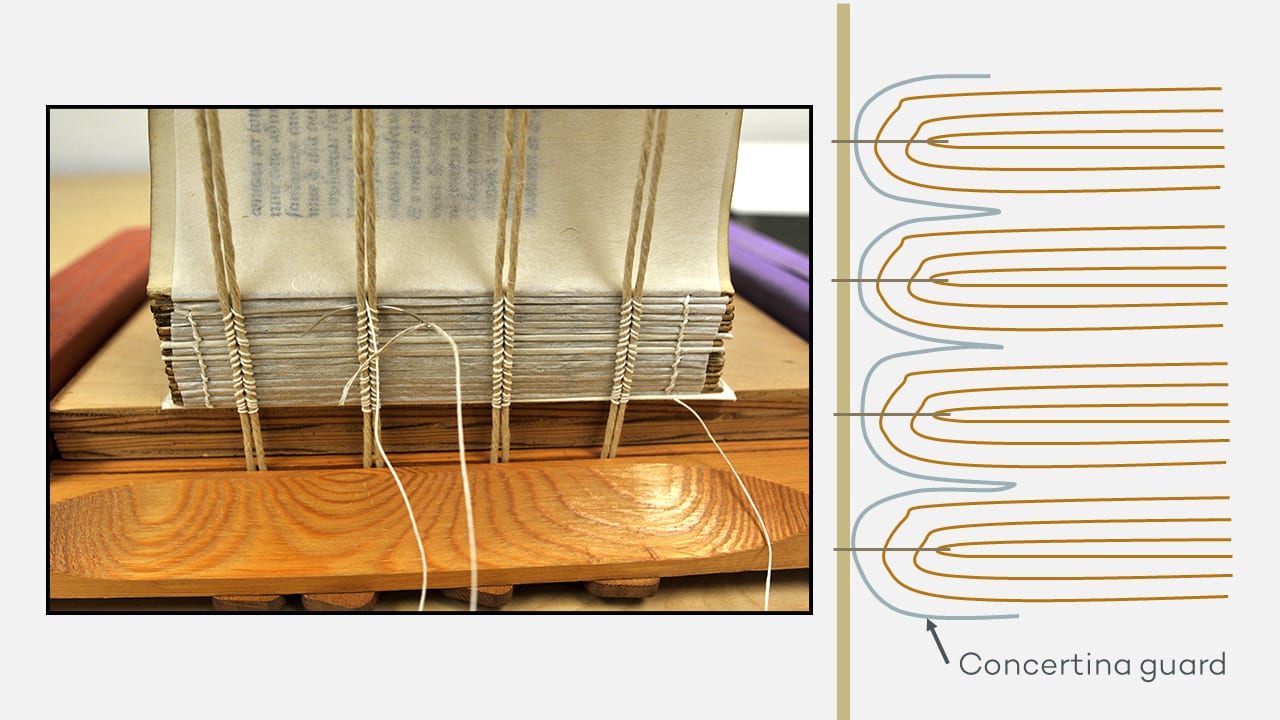

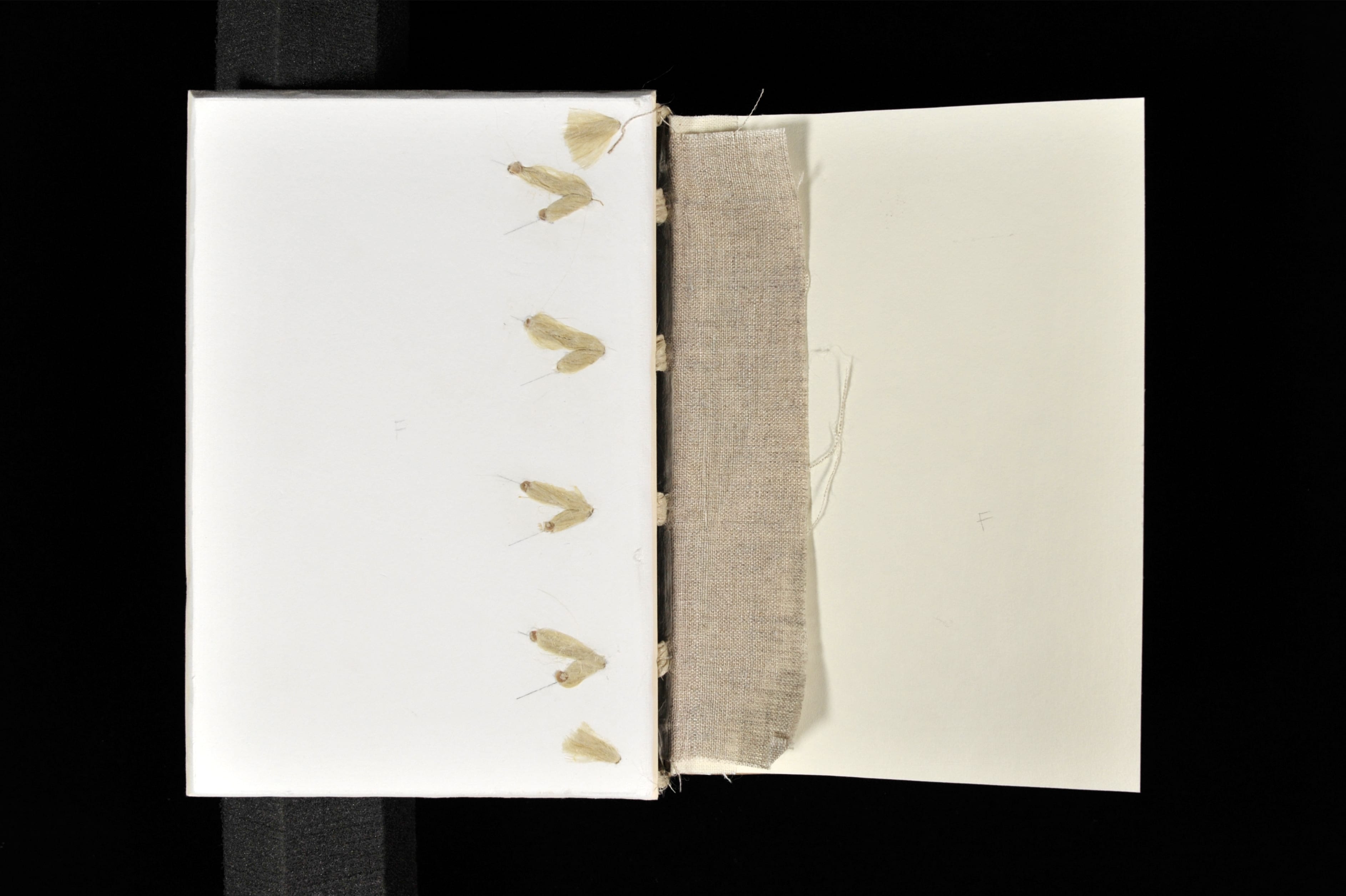

The binding structure used for the manuscript was designed to mimic a Gothic binding style while incorporating conservation-friendly materials and structural details. The parchment gatherings were sewn onto four doubled linen cords using the fifteenth-century sewing stations. A concertina guard of Japanese tissue was incorporated into the sewing. This tissue wraps around each gathering and protects the parchment from adhesives applied later in the binding process.

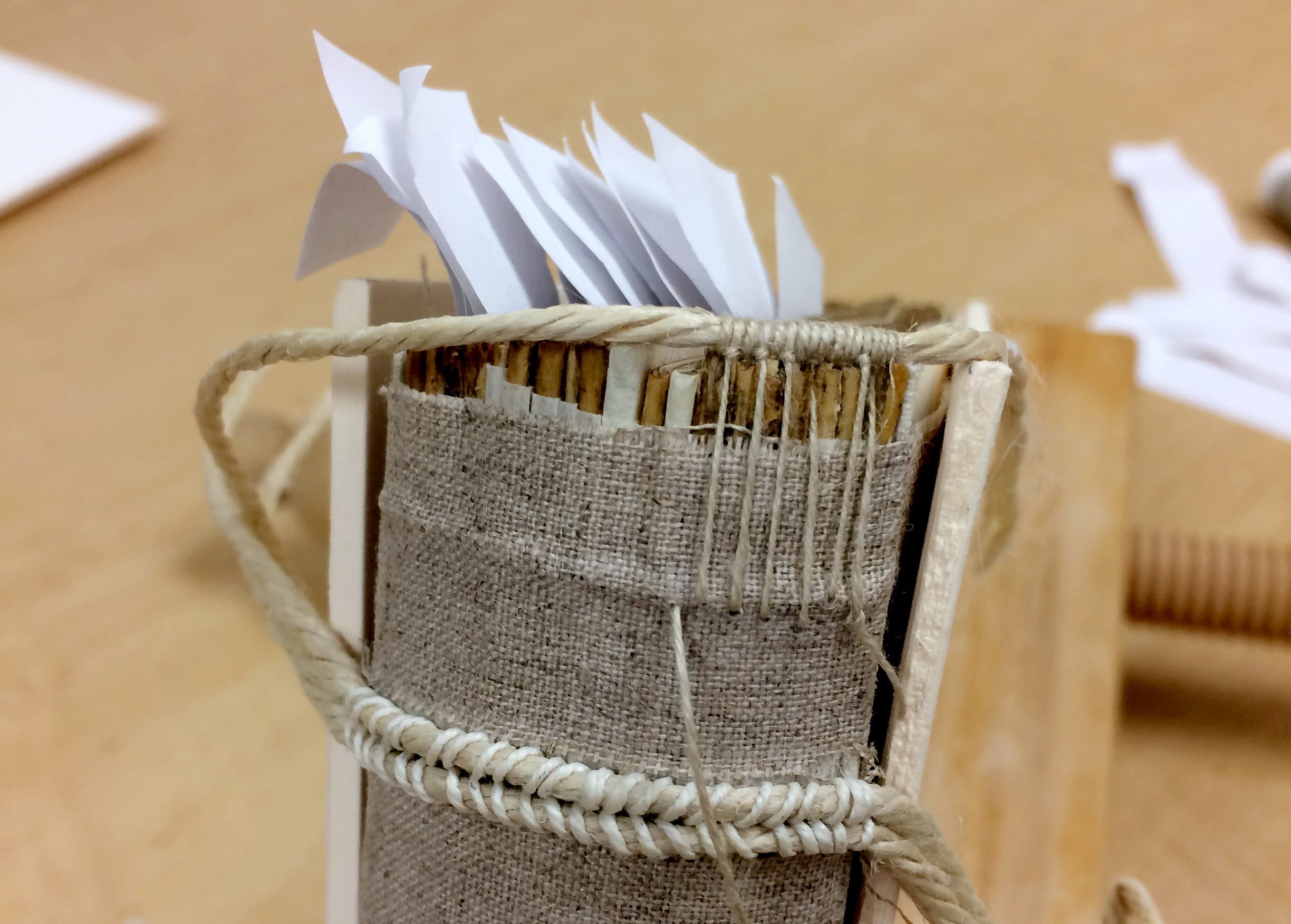

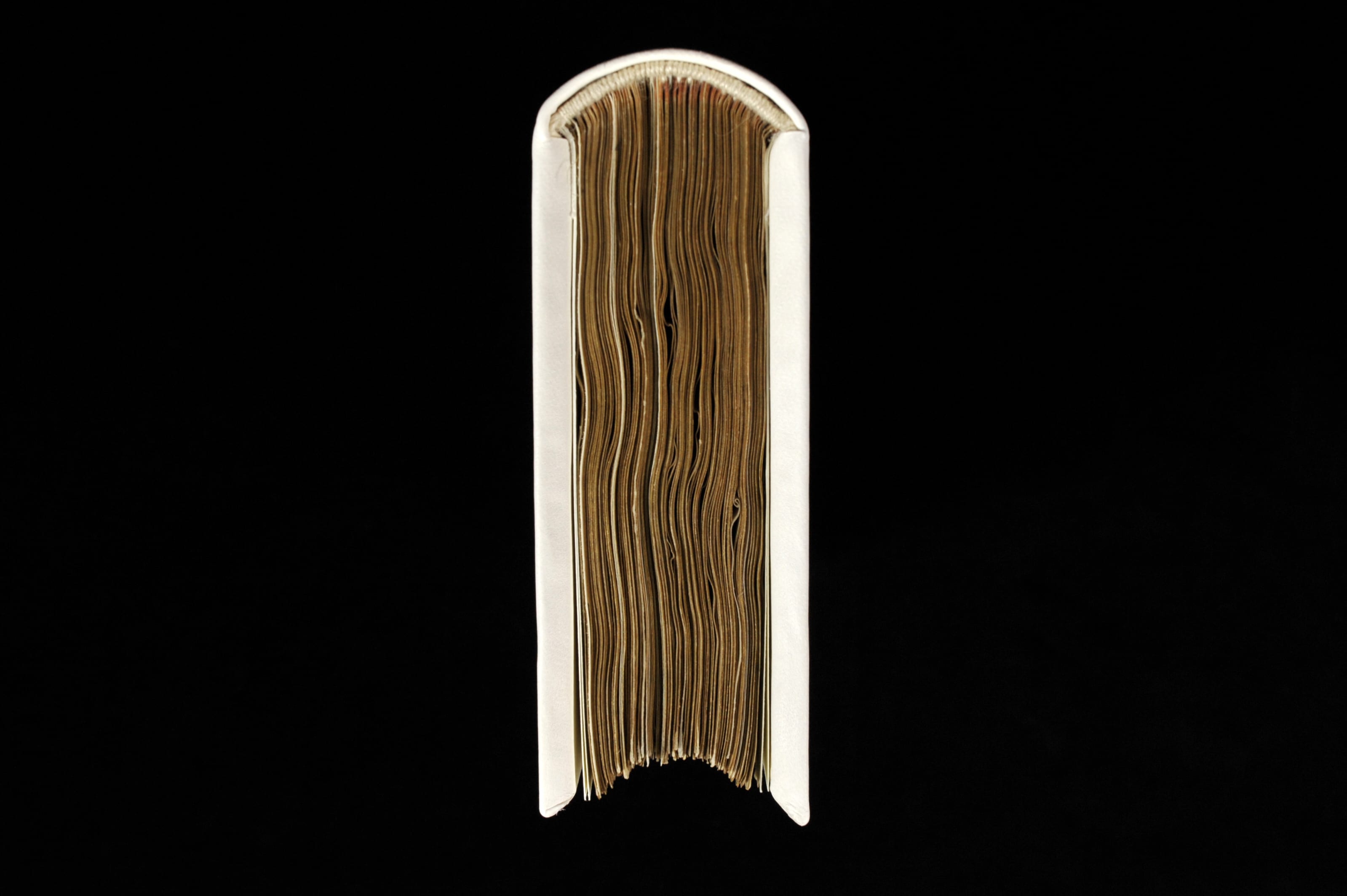

After the spine was lined with aero-linen, simple back-bead endbands were sewn to impart more strength on the text block structure. This gives the spine a gentle, rounded opening action.

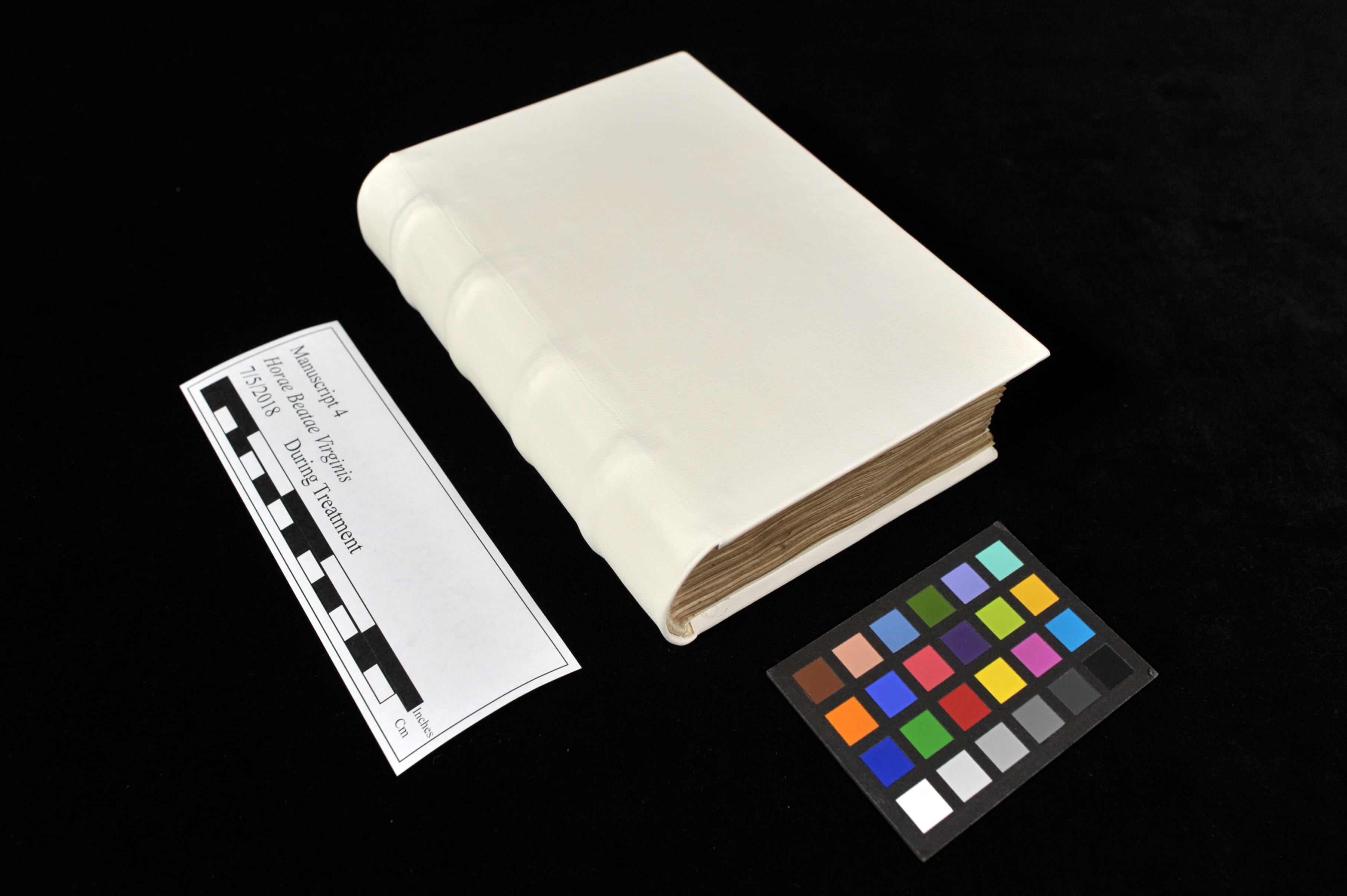

Most Gothic-era bindings possess wooden boards, but wood is an acidic material. To provide a more pH-neutral binding, archival matboard was used in place of wood. The matboard was layered to provide the appropriate thickness, then shaped with tapered edges and channels for the cords. The cords were then frayed, inserted into the boards, and pegged into place.

The binding was then covered in an alum-tawed goatskin. Though the typical gothic binding has a tight-back structure, with the skin adhered directly to the spine, a “baggy-back” structure was used to allow the small binding to open without strain.

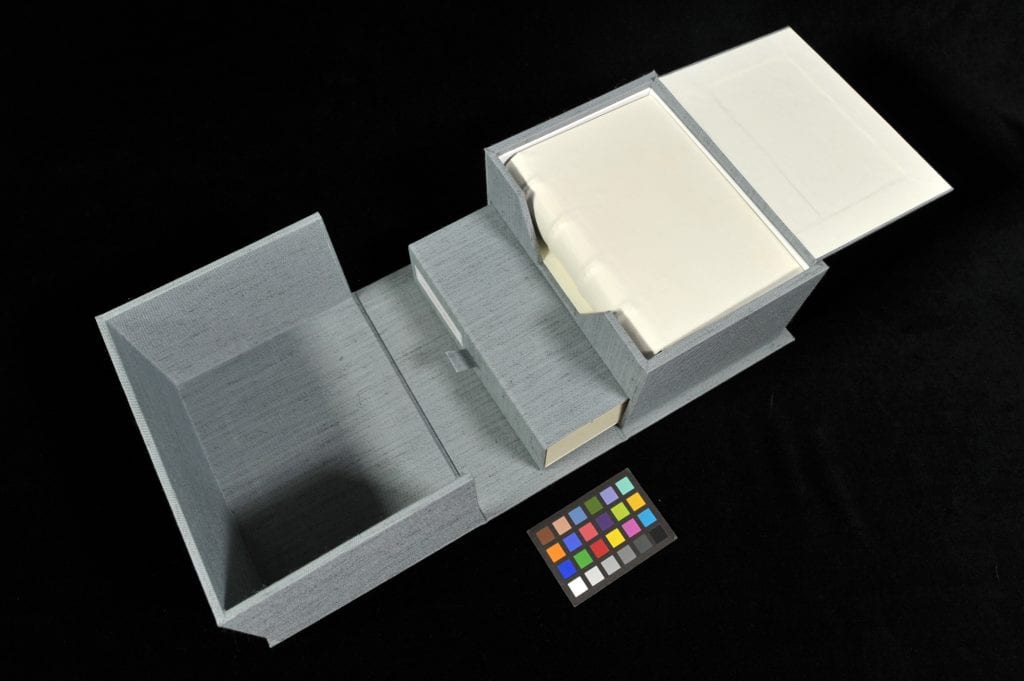

A cloth-covered clamshell box was fashioned to house the manuscript in its new binding. Because parchment text blocks have the tendency to warp and expand, a pressure lid was incorporated to hold the book in its square shape. A secondary compartment was also included to hold the 19th-century binding elements, so we won’t lose that part of the book’s history.