Driving to the O’Hare airport in Chicago, it takes a whopping 1 hour and 15 minutes to travel a mere 8 miles from my wife’s work. The fastest route zig-zags through the suburbs on streets of various sizes and directions. We travel west and south, inevitably hitting every traffic light at every intersection.

Chicago, despite a few cross-cut and diagonal streets, follows a loose grid system. My hometown of Salt Lake City, like most modern cities, also follows a pattern of square blocks. The simple design was originally conceived by the city founders as the “Platte of Zion.” Square blocks and grid systems have since become the standard for urban design.

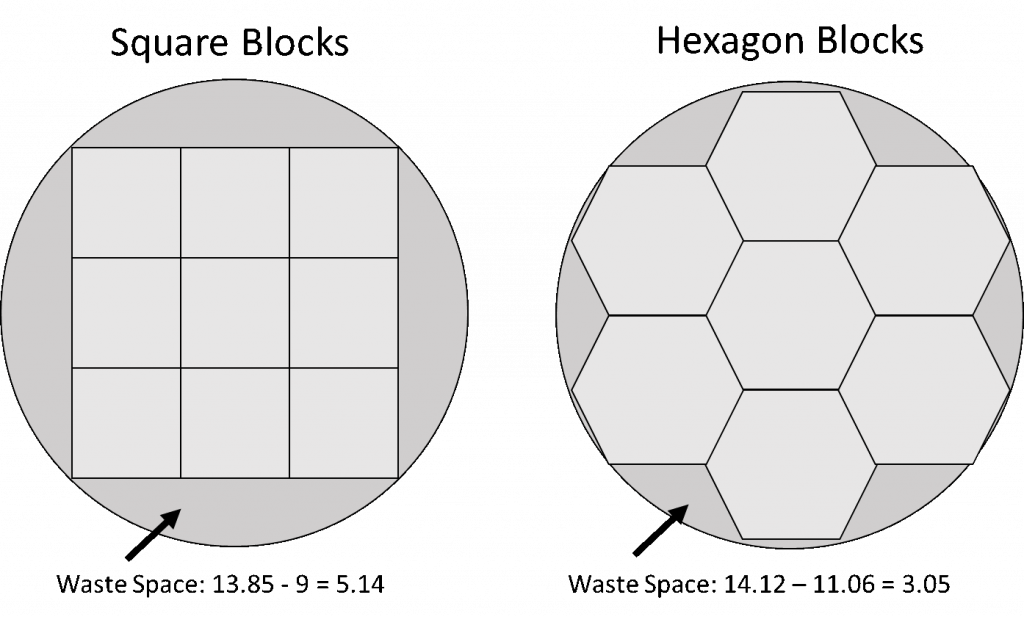

But what if we are wrong using square blocks? Squares and rectangles are very efficient shapes for humans. We put things in square boxes, read square books, live in square rooms and build square houses. However, nothing in nature is square. Rivers wind, hills rolls and mountains come to peaks. As it relates to urban-planning, human expansion is not square; therefore, cities should not be either. Cities are circular. Square boxes are great if filling up a square closet, but are square blocks really great for filling a circular city? To compare, I packed a circle with unit squares* (I found the optimal radius for this circle to be 2.12). I then packed the same circle with hexagons. The square blocks wasted ~5 units of space, while the hexagons wasted only ~3 units.

*Note: this is not the optimal way to pack a circle.

This gave me a thought: what if city blocks were not squares, but rather hexagons? From above, the city would look like the board from Settlers of Catan. Streets would follow a honeycomb pattern (bees are very efficient creatures).

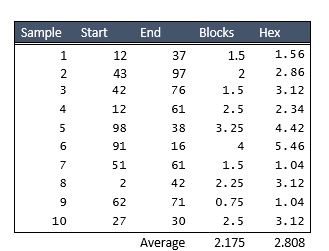

To test the efficiency of hexagon blocks versus square blocks, I need to make a few assumptions. In my test, each city block will have the same amount of departure and arrival points (called nodes). There are no nodes on the corners or intersections. (There may be a store on the corner, but people depart from the edge of the store). Both shapes have the same number of nodes: blocks have three nodes on each side (3 nodes X 4 sides) while hexagons have 2 nodes on each side (2 nodes X 6 sides). Lastly, the area of both hexagons and blocks is the same, exactly 1.

Total Nodes: 108; Total Blocks 9; Block Size: 1; Total Area: 9

Running a simulation with 10 samples on my small 9 block city, it appears that square blocks have the advantage. While this was surprising to me, it does make sense. Despite the same area, my hexagon city is both taller and wider than my block city; therefore, it takes longer to travel from point to point. I would be curious to run this on a larger scale with more city blocks packed into a circle in a different pattern. Perhaps I would get different results if I included every node within a certain radius of my city’s center.

In addition to longer distances, another obvious disadvantage to the hexagon blocks is that turning right and left all the time would make going in a straight line annoying. However, hexagon blocks lend themselves well to the addition of major thorough-fares or highways. On-ramps and off-ramps are already built in.

There is at least one other advantage to hexagon blocks to consider. Three-way intersections are quite a bit faster than 4-way intersections. Vehicles turning right would not need to stop and could have the right of way. Vehicles turning left would have to yield to cars turning right. This would mean a decrease in time waiting at lights.

It looks like a few forward-thinking city planners have already been experimenting with this pattern. I am excited to see urban designs in the future.