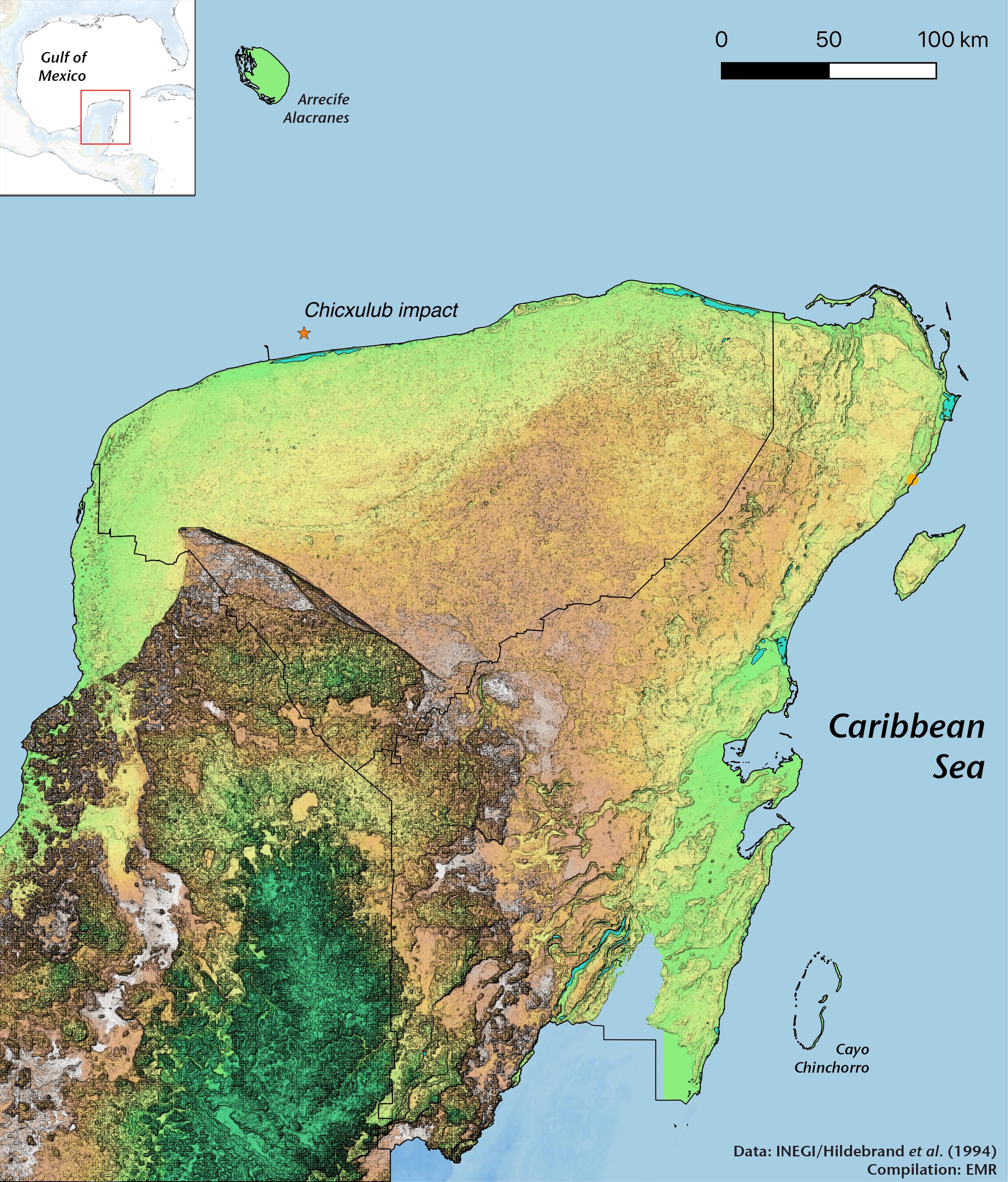

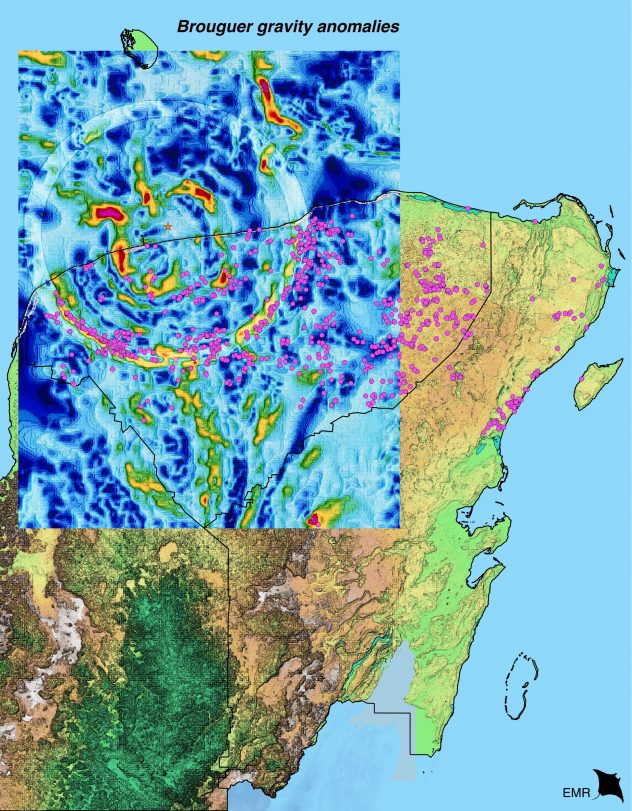

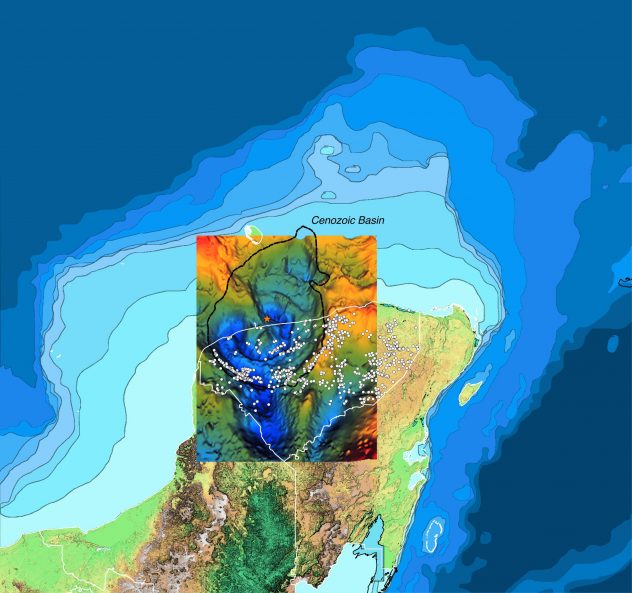

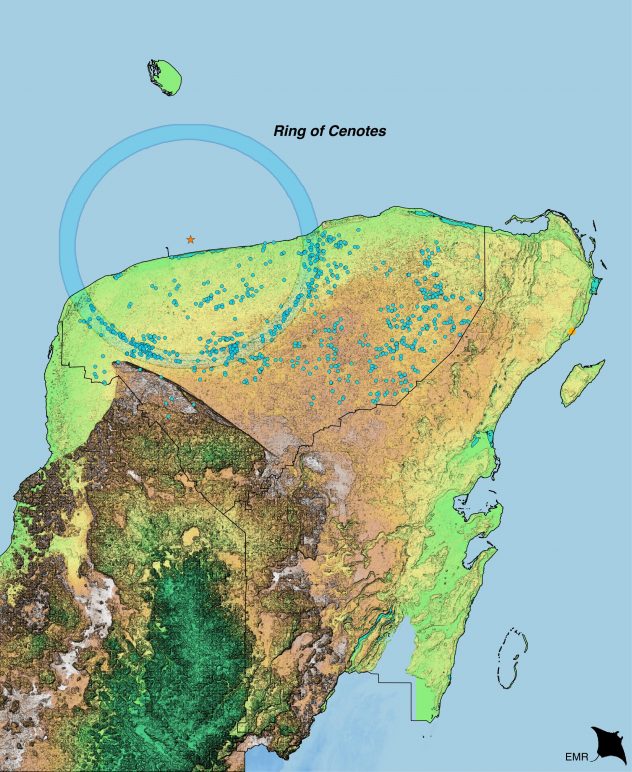

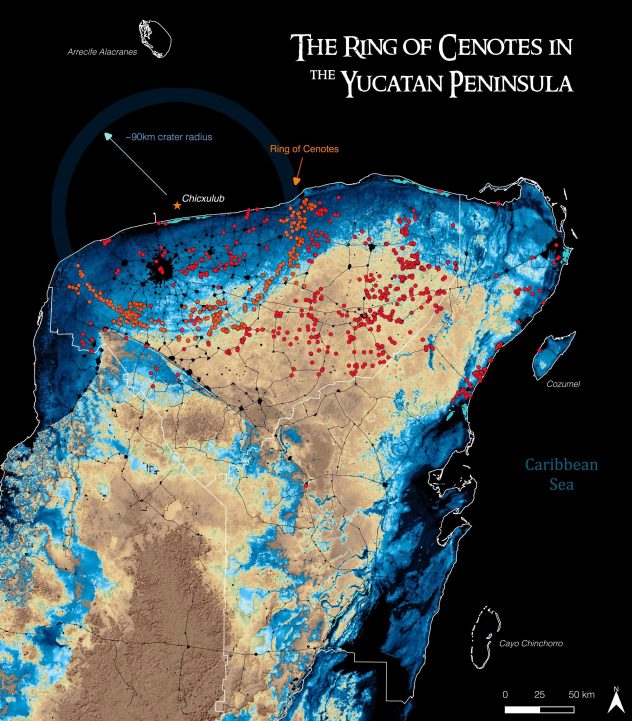

The topographic and geophysical features of the deep impact structure of the Chicxulub crater are reflected on the surface of the Yucatan Peninsula with an aligned arc of sinkholes, forming the “Ring of Cenotes”.

It has been known for almost 40 years that a large meteorite struck the Earth around 66 million years ago in a place in southern Mexico that we call Chicxulub, in the Yucatán Peninsula. It was about the same time that the large dinosaurs disappeared from the Earth. This was a most surprising discovery, since the meteorite crater is extremely well hidden under very thick 3,000 ft (1,000 m) of soft limestone rocks. However, we can see traces of the crater on the surface since there is a great number of very deep and large water filled sinkholes that are aligned along the edge of the crater basin. The local people call these sinkholes “cenotes” (pronounced say-no-tays) in a word tied to the Maya language (ts’ono’ot), meaning “a hole filled with water”.

How is it possible that the crater buried under thick layers of rock can manifest in some way on the surface?

All the cenotes that we know now were formed millions of years after the impact in a much more recent period, probably not more than 126,000 years ago, although it is known that they are related to the geometry of the deeply-buried crater.

There are several hypotheses * about the formation of the Ring of Cenotes (ROC), all of which imply a relationship with the structures, faults and fractures that cross the Cenozoic carbonates, which is the upper layer of carbonates that was deposited covering the crater after the impact. However, there is no detailed explanation of the mechanisms that would operate to create the initial cavities and, more importantly, the mechanism by which the deep crater controls the flow of groundwater close to the surface has not been established either. Another non-tectonic hypothesis but which also implies a relationship with the impact is that which involves coral reefs (leaving more porous and soluble limestone) in the periphery of the “inner sea” (Cenozoic Basin) that was also formed as consequence of the impact, which does not have sufficient evidence.

* I recommend for people interested in this topic to review the information contained in the articles by Pope et al. (1993, 1996); Hildebrand et al. (1995); Perry et al. (1995) and Kinsland et al. (2000).

What is the mechanism responsible for transferring the geometry of the deep crater to the surface, through more than 1 km of Cenozoic carbonates?

Hidrogeothermal Model for the formation of the “Ring of Cenotes”

My research had focused on the mechanisms that allow this to happen. A working hypothesis argues that even before the impact, the heat of the earth caused water to flow through the rock. The impact crater then changed where and how the water could flow, since in the middle of the crater is now a large solid lump of crystal rock formed by the intense shock of the meteorite hitting the earth. Water can’t flow through the crystal rock, so the water now flows up the sides along the perimeter of the solid lump. It is around the sides of the crystal rock where the soft limestone is now even more dissolved, creating large and deep voids. Over time, some of these hidden caves around the edge of the crater and the crystal rock, keep collapsing, and some of them even reach the surface where we can now see them as the Ring of Cenotes.

Recommended readings:

Hildebrand, A. R. et al. (1995) “Size and structure of the Chicxulub crater revealed by horizontal gravity gradients and cenotes,” Nature, 376(6539), pp. 415–417.

doi: 10.1038/376415a0.

Kinsland, G. L., Hurtado, M. and Pope, K. O. (2000) “Detection of groundwater conduits in limestones with gravity surveys: Data from the area of the Chicxulub Impact Crater, Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico,” Geophysical Research Letters, 27(8), pp. 1223–1226. doi: 10.1029/1999GL008404.

Perry, E. C. et al. (1995) “Ring of Cenotes (sinkholes), northwest Yucatan, Mexico: its hydrogeologic characteristics and possible association with the Chicxulub impact crater,” Geology, 23(1), pp. 17–20.

doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0017:ROCSNY>2.3.CO;2.

Pope, K. O., Ocampo, A. C. and Duller, C. E. (1993) “Surficial geology of the Chicxulub impact crater, Yucatan, Mexico,” Earth, Moon, and Planets, 63(2), pp. 93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00575099.

Pope, K. O. et al. (1996) “Surface expression of the Chicxulub crater,” Geology, 24(6), pp. 527–530.

doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0527:SEOTCC>2.3.CO;2.