Was Mayor Richard J. Daley a metropolis-molding tyrant of Caesarian proportions?

This might sum up the view developed in columnist Mike Royko’s unauthorized biography, Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. Published in 1971 by E. P Dutton & Co, the book spent 26 weeks on the NYTimes Best Seller list. Royko won a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary the following year.

Royko himself did not explcitly liken Daley to Caesar. No discussion of Caesar or Caesarism is to be found in the pages of Boss.

Mike Royko at a book signing with television cameras shooting footage for Walter Cronkite’s CBS News. Clipping in Royko Papers, Box 13, Folder 175, Newberry Library, Chicago

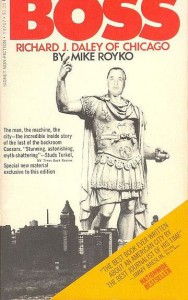

However, the illustration on the original dust jacket (reproduced on the cover of the paperback) and the advertising blurbs for this classic work of investigative journalism suggest precisely that succinct account of the book’s central argument. The image campily pastes Daley’s face on what appears to be a Roman statue of a political leader, and portrays his body, blown up to Godzilla-like proportions, stomping through a Chicago neighborhood.

Was Daley’s ambition to serve an unprecedented fifth term as mayor reminiscent of Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C), the brilliant statesman and overreaching military genius who defied the Roman Senate’s order to step down from his command, crossed the Rubicon and took supreme power — only to be assassinated? Or is he best compared with the first Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.), who ruled as an unoffocial monarch while carefully maintaining a facade of constitutional authority, initiated a period of peace (Pax Romana) and presided over a vast building program that shaped the city of Rome and included critical public works such as the network of roads? In what ways are the Caesars useful for thinking about the complex ways in which Daley was, simultaneously, a great populist, a visonary and a ruthless powerbroker?

The cover art is probably based on a well known 8′ statue in the Museo Nazionale in Naples that is presented to visitors as Julius Caesar. The head on this statue is a modern addition to an ancient body. The raised arm is a restoration as well. The ancient body is in a style a century plus later than Julius Caesar. The modern head was done by a sculptor named Carlo Albacini in the 1790s, and was probably based on a colossal portrait bust of Julius Caesar called the “Farnese Caesar.” The pose of the cover image also recalls a specific, well-known Roman statue of Caesar Augustus known as the Augustus of Prima Porta. That sculpture depicts Augustus as a victorious general and ideal statesman engaged in making a speech.

Perhaps the illustration was designed to capture Daley’s pretensions to be a statesman and supremely effective and praiseworthy steward of public life — pretensions that Royko explores and upends inside his book. And pretensions associated with the spectacular, and spectacularly duplicitous, Caesars.

Studs Terkel’s review of Boss in the NYTimes (April 4, 1971) sums up Royko’s stunning achievement as a brave, direct confrontation with a “Caesar.” Terkel argues that what makes the publication of Boss “a cause for celebration” is its “myth-shattering character.” Unlike other journalism, Royko’s work on the corrupt underside of Chicago politics directly goes after the mayor “Himself.” Terkel writes: “Reporters expose daily horrors and corrupt practices: source, City Hall. Yet their editors and publishers are singularly mute. If fault a man they must, it is a lowly ward heeler, a small-time slumlord or an appointee of the chieftain, never Himself. It is not in their nature to blame this Caesar, let alone bury him, as he bulls his way to an unprecedented fifth term.”

After this review appeared an explicit comment referencing Caesar was added to new printings of the cover (e.g., the Signet copy above). The new blurb announces that Royko’s book exposes the practices of machine-style politics and promises to render Mayor Daley “the last of the backroom Caesars,” a phrase that invokes the entire tradition of power grabbing Caesars that defines the Roman Empire — as opposed to the republicanism that the assassins of Julius Caesar sought to protect.

Why might these links between Chicago machine politics and Caesar have resonated among a public largely unfamilair with Roman history? In the nationalist upheavals of 1920s and 1930s the notion of “Caesar” emerged in the popular discourse as a way of speaking and thinking about power. Illegal immigrant and New York mobster named Salvatore Maranzano took up the moniker “Little Caesar” to indicate a certain Roman spirit of hierarchy by which he planned to run his NYC-based organized crime syndicate; at just the same time, W.R. Burnett published his debut novel Little Caesar, about an Italian small-time crook who nearly makes it to the top of the Chicago mob. A film adaptation of “Little Caesar” set in Chicago starring Edward G. Robinson followed in 1931. In addition, Italy’s fascist leader Mussolini cast himself as a reincarnation of Julius Caesar in the 1930s and throughout the Second World War. For a time the very name Casear summoned thoughts of tommy guns and fascists more quickly than togas and triumphs. In 1953 a brilliant film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar starring John Geilgud as Caesar, Marlon Brando as Mark Anthony and James Mason as Brutus was a huge critcal and popular success, catapulting the figure Julius Caesar into the public imagination. (Read more about adaptations of ‘Caesar’ in a variety of modern media.)

The image of Daley as Caesar also featured in the musical comedy adaptation of Royko’s “Boss” commissioned in 1972 by a Chicago producer expressly to christen the new Forum Theatre in Summit (a Chicago suburb). The play ran in 1973 and goofily lampooned Daley. It presented a series of musical numbers placed in a variety of settings, for example, a St. Patrick’s Day parade and the mayor’s birthday party. Some of the antics involved scenes featuring the actor portraying Daley wearing a costume based on the image on the cover of Royko’s book. One reviewer singled out the musical number with Daley and his fire commissioner “both garbed as ancient Romans in a steam bath, with Ciceronian dialogue to match” as the “one true comic exchange” in the whole production, which flopped.

Mike Royko’s Daley is a willful political world-shaper, a tyrant, and finally a no-good dirty crook. These three aspects of the man—as founder, fearsome tyrant, and crooked machine fixer—are all conveyed in the 1970s through a single reference: the lens of Caesar.

Royko’s hard look at the Daley was also about more than Chicago politics. It was, in journalist Jimmy Breslin’s words, the “best book ever written about an American city.”

Later editions do not reproduce the cover illustration but instead use a photo of Daley. We’re looking into why. Was it a copyright issue or a marketing decision? Does ‘Caesar’ no longer quite resonate in public discourse in the same way, if at all?

(E.O., S.S.M., J.W.)

Pingback: julius caesar the daily northwestern login, make payment, customer service number online - hmaillogin.com