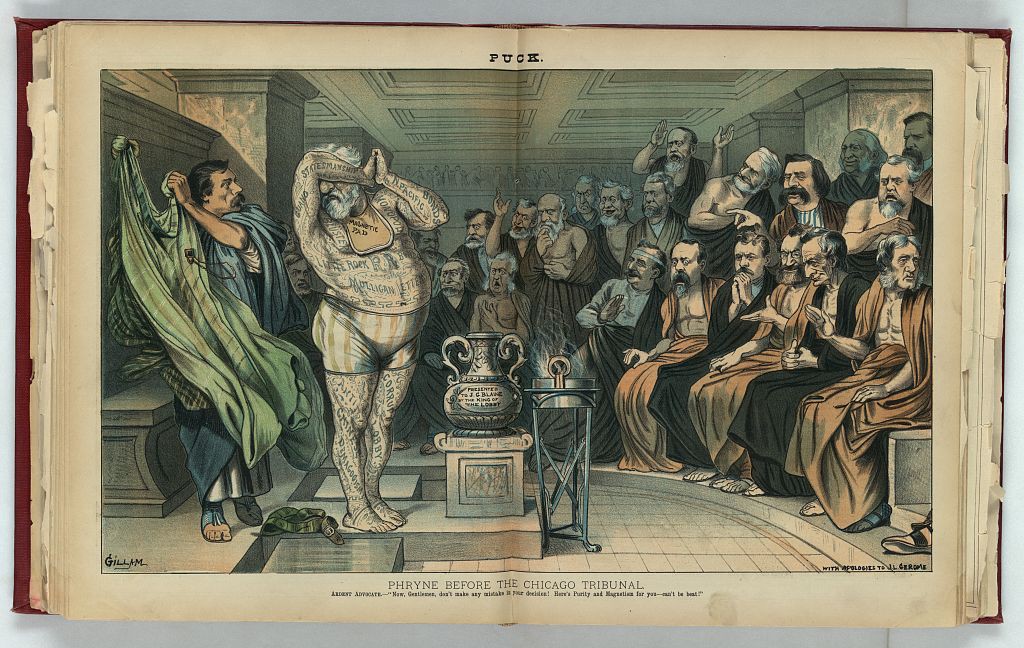

Satirical magazine Puck published this cartoon, “Phryne before the Chicago Tribunal,” on the second day of the Republican National Convention of June 1884, held in Chicago. It shows James G. Blaine (who would shortly win the party nomination but lose to Grover Cleveland that November) being stripped of his clothes before the party, with all the political scandals he was rumored to be involved in inscribed on his body as tattoos. The joke depends on a reference to Phyrne, an ancient Greek courtesan whose lawyer supposedly disrobed her before Athenian jurors—the baring of her breasts led to her acquittal. Whereas Phyrne’s famously beautiful body persuaded them of her innocence, Blaine’s political nefariousness is clearly manifest in his grotesque shape and the legible catalogue of his scoundrelly behavior. And yet! His “Ardent Advocate,” according to cartoonist Bernhard Gillam’s caption, is saying: “Now, Gentlemen, don’t make any mistake in your decision! Here’s purity and magnetism for you – can’t be beat!”

Gillam’s signature at the bottom left faces a note at the bottom left, “with apologies to J.L. Gerome,” referring to the French painter’s 1861 work, “Phryne revealed before the Areopagus”:

Most of our information about Phryne, the infamous hetaira of mid-fourth-century BCE Greece, is anecdotal and not authoritative, coming from Athenaus who was writing over a century later. Her many lovers included politicians and sculptors (Praxiteles apocryphally used her as the model for his Aphrodite of Knidos); she had a habit of letting down her hair and stepping naked into the sea during the festivals of Eleusis and Poseidon; she offered to personally fund the rebuilding of the walls of Thebes on the condition that the words “Destroyed by Alexander, restored by Phryne the courtesan” be inscribed on them.

No account details the charges against her in court; Athenaus only remarks that it was a capital offense and that she was defended by Hypereides—who apparently was a client of hers before she was his. Gerome’s painting originates from a highly disputed legend surrounding the trial—when it seemed she was about to be judged guilty and put to death, Hypereides disrobed her breasts before the jurors, successfully arousing their (ahem) pity, and securing her acquittal. This gesture resonates richly within the classical world: in Aeschylus’ Oresteia, the court of the Areopagus was founded at the trial of Orestes for matricide. Not only is this aitiology steeped in gender conflict—killing one’s mother versus killing one’s husband, Apollo versus the Erinyes, the androgynous Athena as presiding judge—but also, especially in this court, Phryne’s gesture recalls Clytemnestra’s baring of her breasts to stir her son’s pity, which of course did not work out so well for her. Here, however, Gerome exaggerates Phyrne’s exposure as fully nude in a neoclassical style, with the arresting whiteness of her skin appearing counter to her supposedly yellow complexion that earned her the nickname Phryne, which means “toad” in Greek.

With reference to Gerome’s painting, Gillam’s cartoon activates several comparisons at once—the vicissitudes of the Republican convention to the ancient Athenian court, prostitution to politics, moral constitution to physical form. Most of all, the cartoon implicitly represents Chicago as a kind of modern Athens, the country’s central polis where, for better or worse, the most important political action takes place. Chicago is known as “The Windy City,” and the possible political origins of this nickname—due not to its meteorological blusteriness but because of Chicago politicians giving long-winded speeches full of hot air—go back to the mid-nineteenth century.

Blaine himself was nicknamed “The Magnetic Man” for his charismatic public speaking skills. Gillam’s choice to depict Blaine in Chicago only enhances the charges he makes against flashy rhetorical manipulations by inscribing Blaine’s oratorical finesse onto his skin and physically vilifying it. Gillam gave Blaine a bib that says, “Magnetic Pad”—as if, in this politically charged city of all American cities, he might especially want to eat his words? K.H.